We’re doing monthly lunch and learns now—sessions where one of us shares a presentation (over lunch) on something that interests us and is applicable to what we do. Today I presented on “The Web of Tomorrow,” which covered a bit of the history of the web, specifically connecting some of the key ideas that paved the way, and then where I think it’s all going. Here are the slides and a writeup of the gist of it.

I want you to think about the web.

Seriously, close your eyes for a moment and imagine the web—what it looks like, what it feels like. Freely associate. Think about how you use it. Reflect over the memories and feelings you connect with when you think about the web. What do you see?

I tend to see something like this:

Black City, by Julie Mehretu.

If you’ve ever seen Julie Mehretu’s work in person, you’ll know what I mean when I say that it swallows you up. It’s large enough that you can almost imagine yourself inside of it, like stepping into another world. When I think about the web, I almost always envision something that looks like this: the complexity, the chaos, the organically assembling and emerging systems. There is a structure there, but it’s obscured by the energy and movement of information. Rather than something that is all structure—the type of schematic imagery we tend to see in representations of the web, this depicts something that’s alive and bigger than us. While I don’t think that the web is alive, in terms of having a consciousness, it has certainly become bigger than us.

How did we get here?

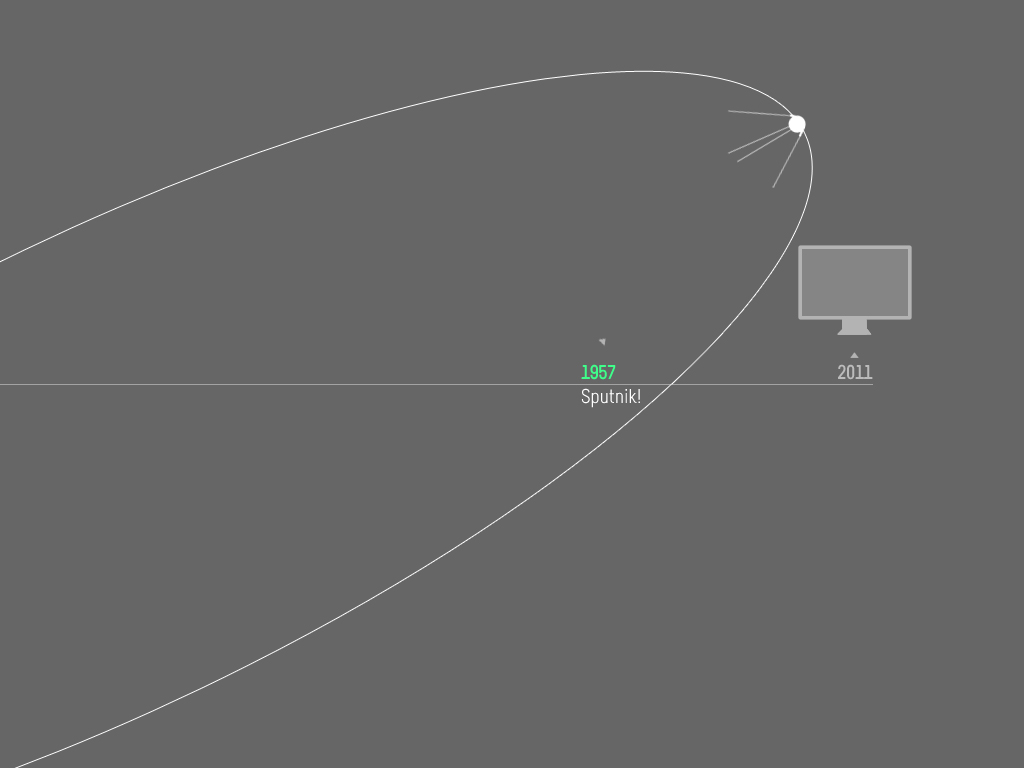

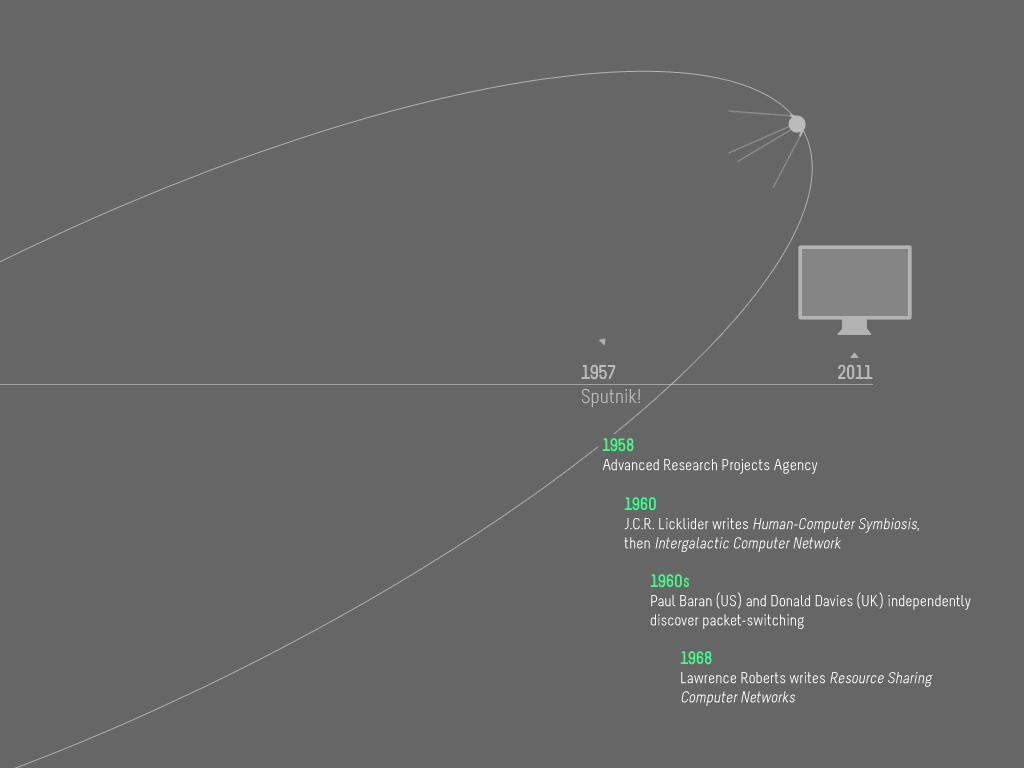

The launch of Sputnik is a critical date in the history of the web, even though it happened over thirty years before Tim Berners-Lee created the first links with hypertext. Without getting in to too much detail (which you can get from the Wikipedia entry on Sputnik), the Sputnik program began with the first completed launch of a human-made object into space and successful orbit around the Earth. The second Sputnik mission carried the first living passenger, Laika, into space. These were Russian missions. Beyond being scientifically groundbreaking, they dealt a significant blow to the American ego, one that was a catalyst for a ten year burst of scientific and creative work without which this web page, Newfangled, and much of contemporary culture and industry would not exist today.

Notice the rapid succession of innovation that came after Sputnik (and by the way, there are many more significant entries that I could have noted, but these four were ones I wanted to highlight for the ways they shaped the web we know today). The creation of the Advanced Research Projects Agency in 1958. Human-Computer Symbiosis and Intergalactic Computer Networks, imaginative and essential writings published by J.C.R. Licklider in 1960 that provided needed vision for how this whole thing would work. The synchronicity of the independent discoveries of packet-switching by Paul Baran in the United States and Donald Davies in the UK. And in 1968, the publishing of a paper by Lawrence Roberts called Resource Sharing Computer Networks. In a decade, the vision for the internet and how it would operate was achieved. Packet-switching, by the way, is one of the more fascinating innovations of this era—one that is easy to take for granted today as every single time you send an email, the information of your message is broken up in to smaller pieces and sent along various routes that emerge in the network and rejoin at the other end. Think back to Black City by Julie Mehretu and imagine it as a visualization of packet-switching alone.

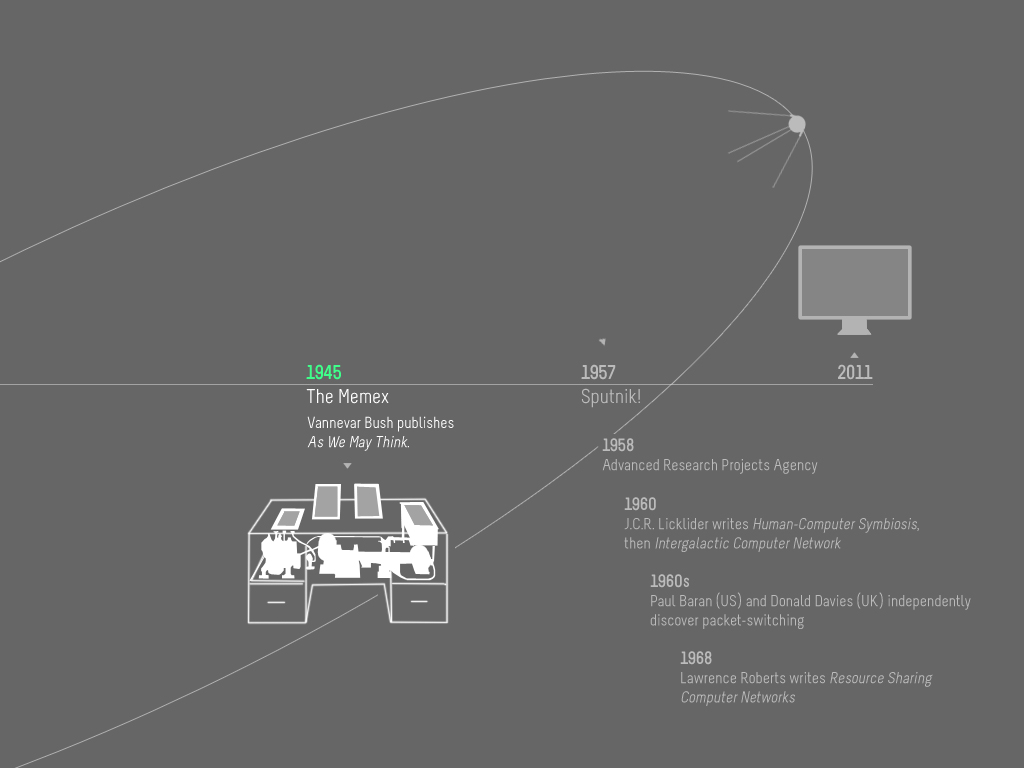

But it’s not as if those ideas came out of nowhere. Particularly, the idea of resource-sharing networks, which is really the idea of making information available to and from anywhere. We can go back another decade and see a version of this in Vannevar Bush‘s memex, a proposed device that would enable its user to store, locally, all of their information—books, files, letters, etc.—which would be retrievable mechanically. Sound familiar? Today, this is something we take for granted with the kinds of computers we use—you know, the ones that fit in our pockets—but in the 1940’s, the idea of storing enough information locally to save you trips to libraries and archives was revolutionary. But again, it’s not as if Bush came up with this completely on his own…

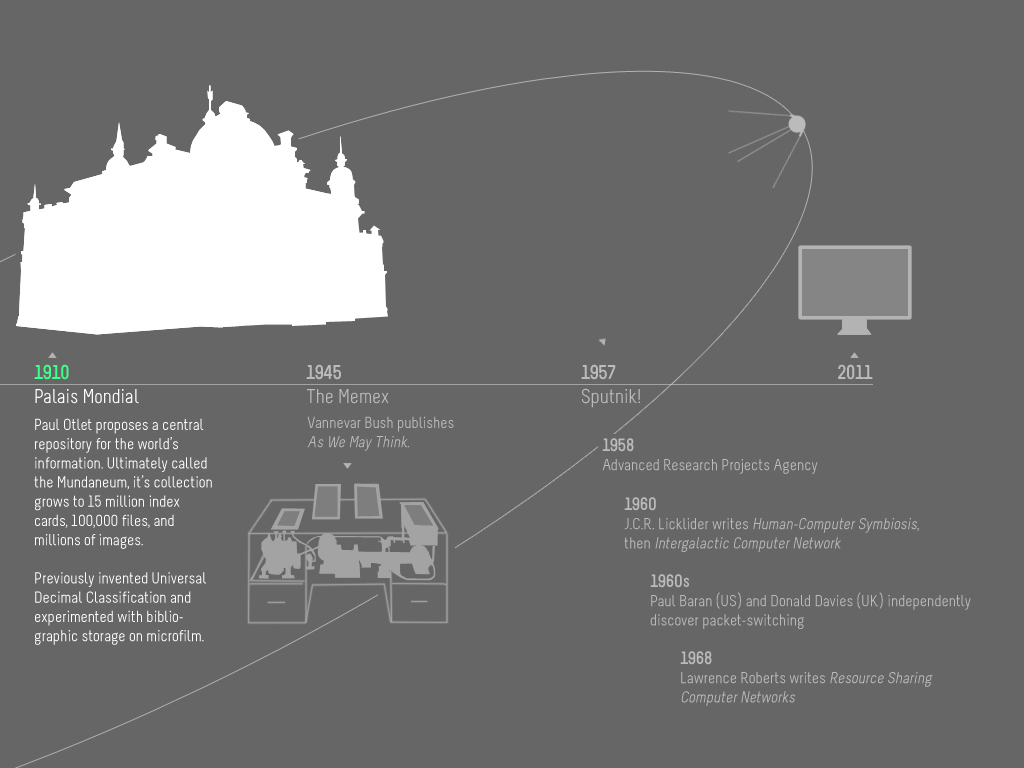

At the turn of the century, French entrepreneur Paul Otlet, considered by some to be the father of information science, had been experimenting and thinking about information in truly revolutionary ways. With colleague Henry La Fontaine, he created the Universal Decimal Classification system, which not only broke down classification by subject, but also used algebraic notation to represent the intersection of subject matter in one text. By indicating that a work dealt with two distinct subjects—say computation and gardening—their system began to explore the links between concepts. Today’s tag-based systems owe their existence to this work. He and La Fontaine also experimented with storing bibliographic information using microfilm (imagine that, scanning books to make them available on screens… sounds a bit like what Google is doing today). But in 1910, Otlet and La Fontaine proposed something even bigger: a “city of knowledge” that would serve as a central, physical repository for the world’s information. They eventually realized this in a building in Brussels, which they called the mundaneum that grew to hold over 15 million index cards, 100,000 individual files, and millions of images.

As I see it, these are some of the big new ideas that provided a foundation for the internet and how it would be used, particularly those that came about in the years between 1968 and 1989, when Tim Berners-Lee created the world wide web. But why did it take that long? When you read the descriptions of Otlet’s mundaneum or Bush’s memex, they seem so close to what we know today. What they were missing wasn’t the function of the system but what it means that information is incorporeal. Both of their ideas localized information in physical forms. But the web today is based upon virtualization of information—not sheets of paper, but bits on a server. Tim Berners-Lee made the conceptual leap and connected the early ideas of Otlet and Bush with the post-Sputnik innovations of Licklider, Baran, Davies, and Roberts (and many other people I didn’t mention).

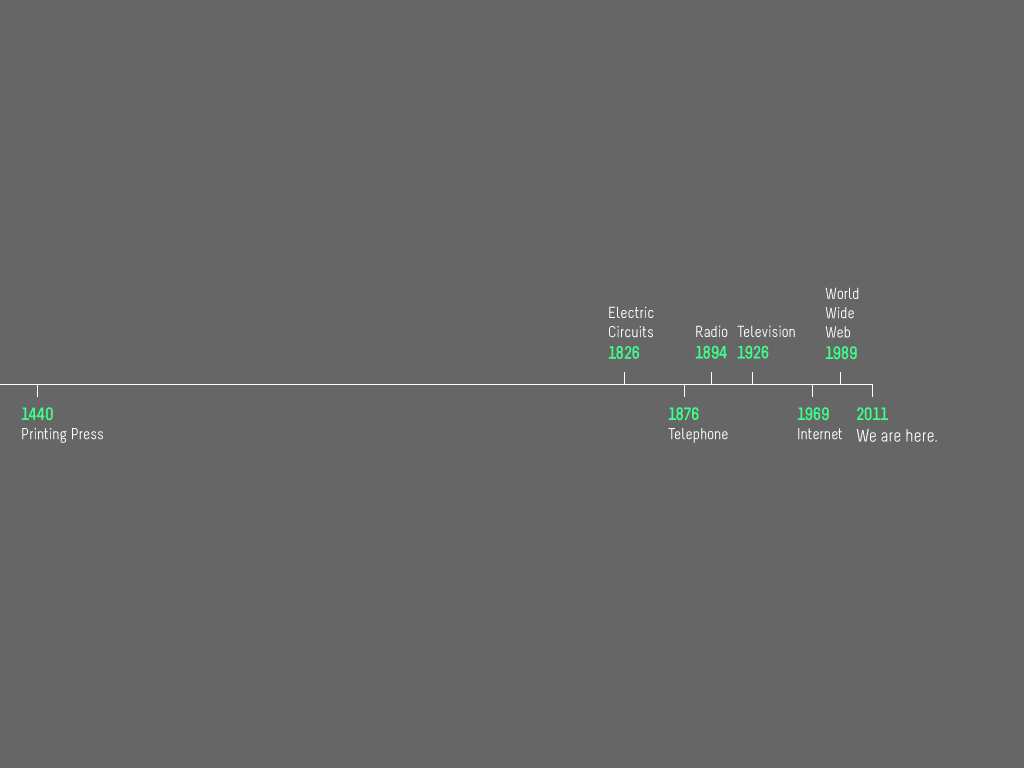

The invention of the web is often compared with the invention of the printing press, both having a radical, sweeping effect upon culture and technology. I noticed, though, that when you plot the timeline of communications technology between each invention, a significant burst doesn’t really happen for over 400 years after the printing press, which was really made possible by the discovery of how to control electricity. Put in perspective, our understanding of the web, and what is possible with internet technology, is still very new.

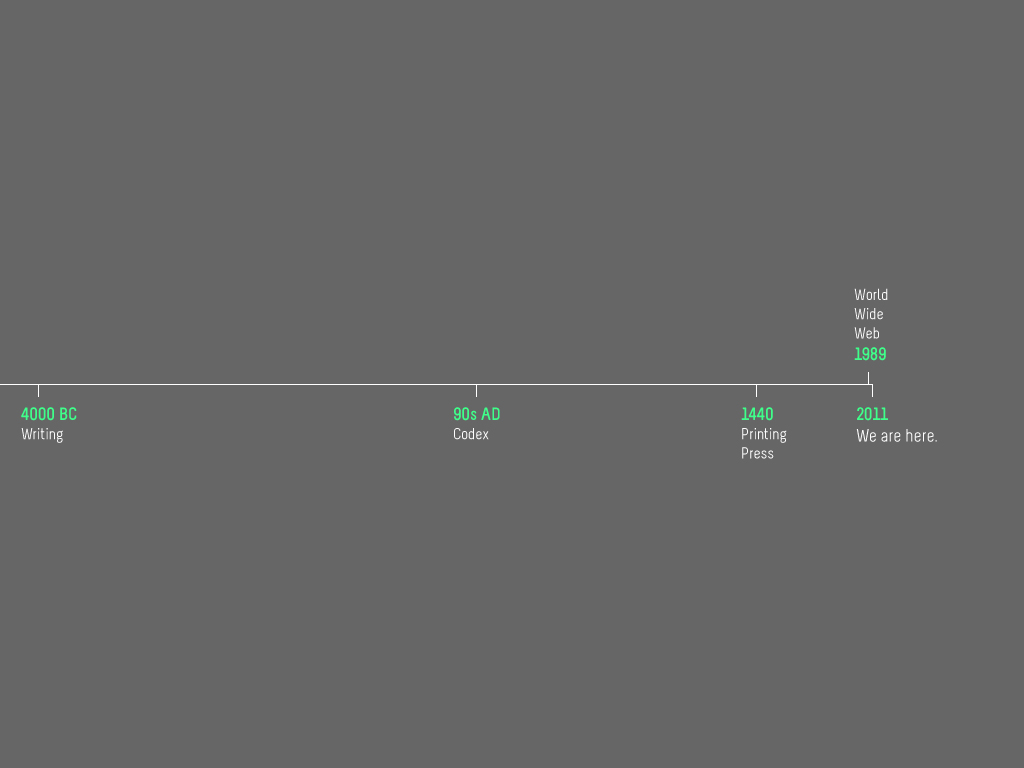

Zooming out even further, we can see that the progress of communications technology, from the first writing to today, was even slower. It was over four thousand years after the earliest writing when humans discovered that the documents they created could be organized differently—from on discreet surfaces like stone/wax tablets and scrolls to collections bound in a codex. After that, it was over 1,300 years until a technology was created that could replace hand-copying of texts. From there, almost 550 years until the web. The spans of time are shrinking. On this image, the creation of the web looks even newer than before.

The web is still so very new. It’s only 5 years older than our company. The rapid change of ideas and technology that brought us to the present, which we can see more soberly than ever on these timelines, should remind us that the way was paved by the clustering of new ideas and enabling technology from previous ones. So, what we conceive of today—what we think the web is and the best ways to use it—coming from only 15 years of small idea clusters, iterative technological development, and a whole lot of trial and error, will change.

Everything we do today will change.

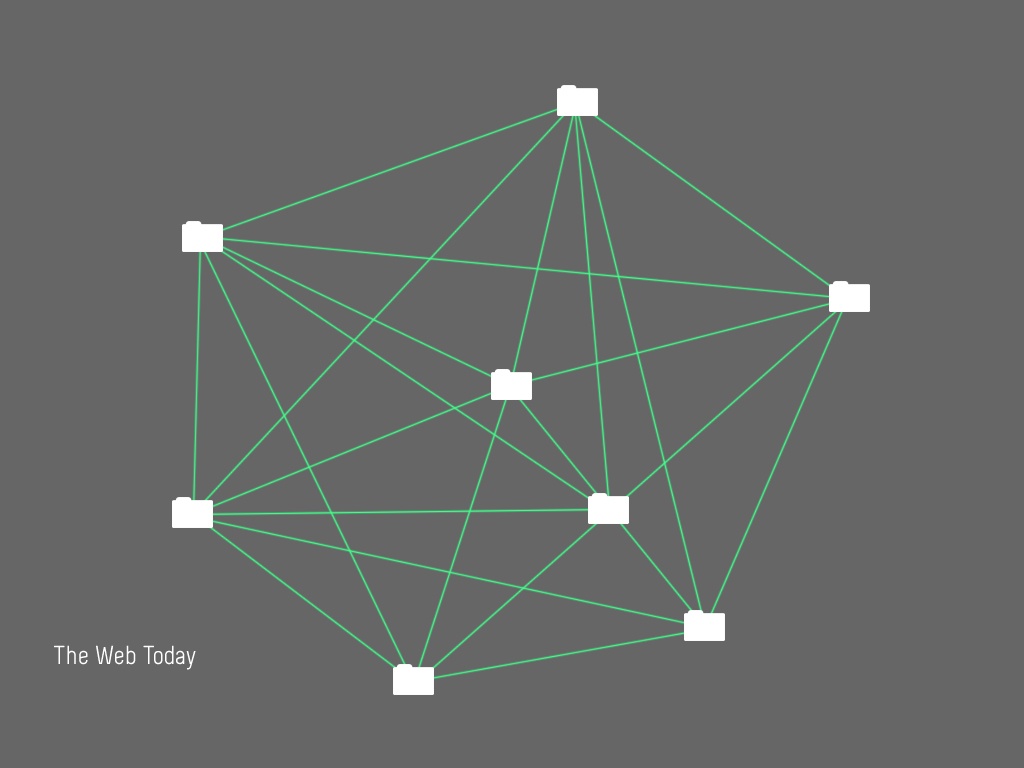

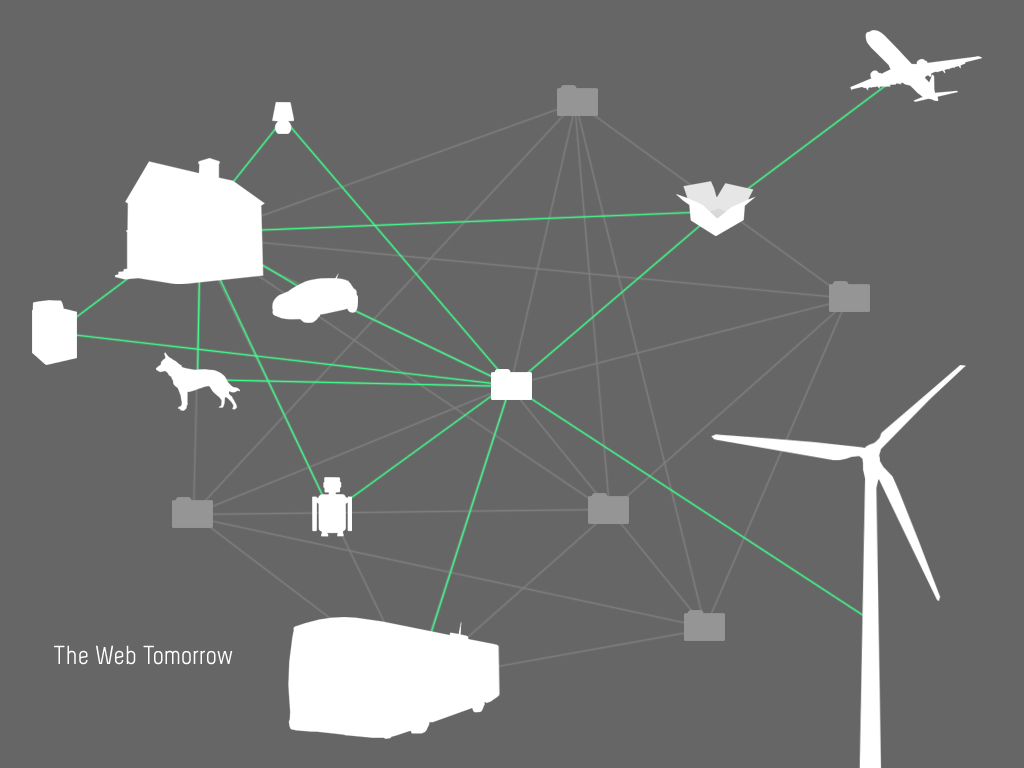

So let’s go back to thinking about the web. In its most basic form, it’s a network of connected files, which looks something like this. What will it look like 15 years from now?

This isn’t so much a prediction as it is a recognition of existing trends, but the web of 15 years from now will most likely be one that has been integrated with an already growing invisible network of objects. I started thinking about this when I imagined the future of the web for a two part article in the summer of 2009 and then later expanded upon in a post for Smashing Magazine on holistic browsing technology, but have been thinking about it even more lately. We’re talking about a major shift from a web that’s primarily interested in the data we create voluntarily—our thoughts, statuses, friends, tags, music, video, conversations, etc.—to a web that will result in a new wave of data created by our things. Our homes alone will be a connected profile web of data-sharing devices: energy systems, lighting, appliances, water filtration, cars, even our pets. Outside of that, buildings, electrical grids, transportation systems, mail and packages, and, yes, robots (lots of robots). In fact, what is the real difference between washing machines that can learn your wardrobe over time, run washing routines based upon what clothing you load into them, and collect and report back to their manufacturers usage data in realtime and robots? Many of our household items are becoming robots. I could write an entire post on robots, but there’s plenty out there on that…

The point is that this new web of objects will begin to gather mountains of data—more than ever before—that will be essential to understanding what marketing messages are relevant to the consumers who purchase these objects. How do they use them? What does that tell product designers, manufacturers, and marketers about how they can improve their products? Even for those of us that tend to build more websites today that say things than those that do things, the invisible web of objects will be just as important because it will be important to our clients. Think about it: the most notable technological progress we’ve seen in the last decade has been within screen-based devices—televisions, computers, phones, and tablets—because that is where our attention goes. And that has been where marketing messages have coalesced, in trying to understand our attention. But meanwhile, progress is also being made in enabling connections to devices that we value precisely because we don’t have to pay much attention to them. In fact, the more “intelligent” these devices become—energy systems that monitor their own input and output and make selling back to the grid easy, self-guided cars, that washing machine I described, and many, many others—the more valuable they will be to us. This web is growing even now and will begin to deliver data to us that we need to be ready to receive.

Are we open to that change? Are we doing enough to prepare for how our business will change as a result?