This past Saturday I had the honor of closing out this year’s Entrepreneur Mindshare at my alma mater, the Rhode Island School of Design. It was a true pleasure to be a part of this event, which included brilliant minds, lots of ideas, and some beautiful enthusiasm. To be honest, I was a bit apprehensive of my involvement, because I’ve never really thought of myself as an entrepreneur. But as I’ve explored the idea, I have come to realize that entrepreneurship isn’t just about ownership — of ideas, of companies, or anything else, for that matter — but about enacting change. When it comes down to it, entrepreneurs want to enact change and have an impact, which is something that can be done by starting something completely new, or by revitalizing something that already exists. My experience has certainly been in the latter. Here are my thoughts on that…

A little over a decade ago, I started my own business. Not knowing any better, I named it after a project I did in my final year here at RISD. So I had my own business (cool, I’m an adult!) but it had a long, embarrassing, trying-way-too-hard-to-sound-smart name (nope, still a kid!).

I have decent ideas, but I’m bad at naming things. Woe to my future children…who will be picked on. Hopefully I’ll have some help with that!

My business was design. So, pretty much whatever. Logos, identity systems, UI, websites, brochures. It didn’t really matter. It was exciting to finally be paid! At RISD, you work all the time, so it was natural to continue this way of life. So, I worked all the time. But this time, paid!

Everyone around me was encouraging. I might even say impressed. See, graduating in the early 2000s was a lot like it is today. Lots of hungry and debt laden students competing for a comparative few paid positions. It was very common to be a “designer” while at the same time being a “barista” or a “guy who puts chicken wings in a bag for you.” I did that last thing, by the way. There were few viable alternatives if you wanted to make any professional progress while still doing important things like eating and having clothing. So to have started my own business was, to the onlooker who perhaps had not, pretty impressive. The fact that I had clients — lots of them — who paid me — more on that in a moment — made me the Donald Trump of my cohort.

None of you is looking skeptical enough right now. Even after I picked the most ridiculous example possible!

Anyway.

One day a friend stopped by my office while I was putting some invoices in envelopes. On my desk were also a few checks that had come in — real professional checks. You know, the kind that don’t have any handwriting on them. He saw them and practically fell off the edge of my bed, where he was sitting. Because by “office” I also mean bedroom. Like I said, Trump. But he was impressed. There in front of him was the evidence that I had pulled this thing off. That I was making real money. That I was successful.

Over the course of that first year, several friends saw what I was doing and similar glimpses of what was for them a good enough indicator of success that they followed my example and started businesses of their own. This did not make me feel like a bishop of design entrepreneurship. It made me feel worried. It made me feel like a liar.

See, behind the perception that they had of what I was doing was the truth.

Their perception was that we were special. That we had brilliant ideas, talent to realize them, a tireless work ethic, and the drive to form all of that into something entirely our own. Their perception was that I had done that already and was well on my way to reaping the rewards. They looked at me and interpreted my life on the basis of three important factors that skewed their perspective.

- Worldview: They — we — had already been indoctrinated to revere the independent innovator. We learned at RISD that there was nothing we couldn’t make ourselves, nothing we couldn’t invent or improve. Outside of RISD’s walls was a culture that worshipped the big idea and, naturally, the big ideator. This was our worldview, meaning, this is the lens through which we looked upon everything.

- The value of reputation: I didn’t correct them when their observations were wrong or their praise unjustified. I wanted to be successful, and in our economy, reputation precedes riches. In the meantime, I’ll be honest: It made me feel good to be admired.

- Inexperience: My friends didn’t know enough to be able to look at my life and their perception of it and see where things didn’t add up. It’s not like I was hiding some terrible secret, but Donald Trump probably doesn’t have a desk in his bedroom.

The facts were these: Facing graduation and an intimidatingly sparse field of employment options, I started freelancing midway through my senior year. I realized this approach would be far less risky than moving out to LA and looking for entry level work there — something plenty of my classmates were doing. Ultimately, this was just an act of cowardice.

Hey, I’ve got to be honest — my parents are here!

So, I registered a business name and kept going. I made OK work. Most of my clients didn’t value design. And why would they? I was cheap. Even so, it was a major effort to stay busy. I’d work 80 hours a week just to bill 25. I barely managed my finances. I probably earned just enough to transcend the poverty line. Everything I owned could fit in a couple of suitcases. I’d bike to client meetings. After my bike seat was stolen, I still biked to client meetings.

Not exactly an impressive sight.

After a year or so of this with not a whole lot of change, I realized that I was probably already looking at the ceiling if I didn’t find some way to learn what I clearly didn’t know. Basics of design business, like project management, client services, financial measurement, marketing, sales, etc. I was just winging it, and I knew it.

This epiphany came at an opportune time. I’d been doing some work for a guy who owned a small company right here in Providence. We’d been meeting up for coffee here and there and talking about design and business, which I saw as the beginning of a mentorship. I thought he was going to be my learning opportunity. As it turned out, he was recruiting me. I resisted this at first, thinking that it would be a compromise to walk away from “my thing,” from my autonomy. But somehow I managed to look at it clearly and realize that taking this new “job” was a necessary step in humility and toward learning all those things I knew I didn’t know.

That small company was Newfangled, where I still work today. It’s where I’ve learned everything I know about business and design. It’s where I’ve truly been able to be an entrepreneur, despite it not necessarily fitting the standard model for that. Actually, it’s where I’ve learned an alternative to the model of entrepreneurship and success that we’re sold on a daily basis.

I think you know the one I mean.

It sounds a bit like this little story.

“Once upon a time there was an entrepreneur. As a child, the entrepreneur was different from the other kids. Strange, even, but in an almost magical way. The entrepreneur was fiercely independent and creative. This sometimes got him into trouble, because the entrepreneur resisted being restrained by rules and his ideas were often misunderstood. The entrepreneur was lonely, but his dreams kept him company. The entrepreneur grew up, and grew ever more driven. The entrepreneur was always creating new things and people began to follow him. Sometimes the entrepreneur created things that were so new, the people had to learn to need them. The entrepreneur built an empire upon this and was rewarded. Everyone admired him.”

OK, OK, so I’m mocking it a bit. But this is a fairy tale. It’s a story we tell over and over again. And yet, it’s really not true. It doesn’t reflect reality — not for those who are or have been successful, nor for those who are headed in that direction. It isn’t my story, and probably isn’t yours.

Let’s look critically for a moment at this sort of person that our culture has deemed fit for representing entrepreneurship and business success.

This person is creative. This person has original ideas. So far so good. This person is aggressive in promoting them. This person creates complex systems to transform his idea into something that can be efficiently produced at mass scale. Getting more complicated now! This person knows how to make it desirable. This person is inspiring. This person is cutthroat. This person sets extremely ambitious goals, methodically reverse-engineers them, and takes only the most efficient steps toward achieving those goals, which typically results in fortune and glory. This person does it again. And again.

Chances are, you are not this sort of robot.

Don’t worry, not many people are!

First and foremost, few people possess all of those strengths in equal measure. I know many brilliant people who, while they can certainly wrap their minds around the detail managed by various roles in a company, are happiest, most productive, and offer the most value to the big picture in cooperation with others. Or, in other words, focusing on the things they do best while relying upon others to do what they do best. It’s no coincidence that many of our treasured entrepreneurship stories begin with two people, rather than just one. It was Jobs and Wozniak; Gates and Allen; Brin and Page. I could go on and on. So why is it that despite the facts of history, we think that the successful CEO goes it alone?

Thankfully, many startup CEOs are coming clean about their struggles meeting their own expectations for what success might look like — there have been many op-eds along these lines over the past year. It’s not just that this sort of thing is hard — of course it is — it’s that the cultural narrative we’ve settled on is uninhabitable to most real people. Even the capable, sincere, and highly functional people from whom you’d expect great success to come easy. This may mean that whatever few cases do fit the narrative of the go-it-aloner — and they are very, very few — are not only the result of a variety of disparate factors glued together by luck, but also a very unique, rare, and quite possibly unappealing personality. You may want what these people have, but would you want to be them? There is an important difference there.

So it’s rare that there’s a sole hero at the center of these stories. But what about the plot structure itself?

Well, the linear component to the typical narrative is also misleading. And, it tends to be the thing we hear most about — the so and so never looked back and powered through story — and so we wrongly conclude that it’s a normative path to success. But it’s not. Realistic success narratives are much harder to string together because they’re ad hoc. They’re a long, curvy, choose-you-own-adventure style story of I did this, which led to this, which led to this, etc. But a simpler story, one in which I was certain that wanted this and so I relentlessly powered through to get it, is much more exciting and likely to cut through the noise.

But aren’t the ad hoc stories, in the end, more interesting? Isn’t there more mystery there? And isn’t at least mentioning the role of that mystery in our success narratives a more honest representation of reality?

After all, the mysterious twists and turns of reality don’t preclude your success or your failure. They’re simply the terrain. How you navigate them is the story you will tell. And the inherent diversity of the mysteries that will shape your life is a gift to us all, because they make plenty of room for nuance when it comes to defining how to achieve success, or even what success is!

You don’t have to try to reverse-engineer the paths of the Steve Jobses out there. In fact, it’s better that you don’t, because it probably won’t work. It’s not that there aren’t valuable things you can learn by studying heroes, but you have the luxury of looking at their lives in hindsight, going from effect and back to cause. They didn’t, and you don’t either, when it comes to your own life.

Rather than trying to build a program for your life based upon the events of others’ lives, why not build a program for your life right now, based upon values you can embrace and trust will bring about good things in your life, and the postures you can take that put those values into practice.

What might that look like?

Well, I’d like to share with you 8 bits of somewhat random advice that I think might help you realize your vision. These are not going to be about how to be creative or have good ideas. I think you’ve probably got that under control…

Let go of “entrepreneurship.”

Focus simply on having an impact. There’s really nothing else to add to that.

Learn to perceive opportunity.

Everyone loves the life-as-story metaphor, myself included. But be careful to not go off the deep end and subscribe to a truly nutty belief like that you are the writer of your own story. A writer imagines a narrative with a start and end point and then systematically builds a plot that connects the two. We don’t do that. We stumble along the path blindly, learning as we go. You can’t write a story and experience it for the first time simultaneously. So which is more true of your life? Are you the writer, really, or the protagonist? It makes a difference.

When I was offered the job at Newfangled, I could have said to myself, “no, mine is an entrepreneur story. the next chapter can’t be working for someone else.” But my goals, thank goodness, weren’t that specific at the time. They were to learn, to survive. I had the desire to be successful, which essentially just meant somehow gaining more influence and money than I had at the time. But I had no specific commitments to how that might be achieved.

In other words, it was about perceiving the next opportunity, not necessarily the final one.

This doesn’t mean that having an end-game in mind is wrong. It just means that you should realistically have a few end-games in mind, but a much more defined next step in place. You need to learn to run scenarios so that you can avoid the bad ones and encounter the good ones without brute force. Think of these as scenarios I can live with vs. those I cannot.

Have a loose agenda for life. It’ll make it much easier to have an impact!

Experimentation results in being wrong, which is why you do it.

The thing that most disappoints me about our industry is that nobody really accepts experimentation. It’s ok if it’s part of a coolness doctrine — a-la Google’s 20% thing, which, by they way, they’ve tossed out — but when it comes down to real, deliverable working relationships, experimentation is practically anathema. For a design-school graduate, this is terribly annoying.

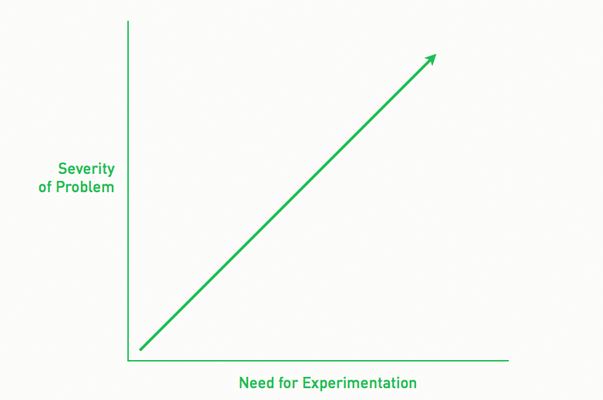

Because there is a professional spectrum along which expertise and experimentation lie. The variable that moves along this spectrum is the problem you’re trying to solve. As the problem grows in severity, the necessity of experimentation increases. Simple! Law knows this. Science knows this. Medicine knows this. In those areas, if you have a minor problem, like a small claim or the common cold, you’re going to get a rather boxed solution. But if you bring a truly severe problem to their office, the first thing out of a doctor or lawyer’s mouth will be, “We can try this…” But marketers? They haven’t gotten the memo. And if you’re a designer, you’re probably working with marketers.

So your job is to work experimentation back into the professional vocabulary. Experimentation and confidence are not mutually exclusive, so we’ve got to be honest when we’re trying something. If you say “try” with even the slightest apprehension, don’t expect to be given the chance. But believe in “try,” and you will.

Be platform agnostic.

I’ve designed for print, interactive media, the web, and now, my colleagues and I spend a lot of time doing what I can only describe as information logistics. Meanwhile, I’m keeping an eye on all kinds of things — like RFID, speech to text, and the like — that don’t yet impact our business but probably will. We all sit at the nexus of a variety of cultural, technological, and economic trend lines that will ruthlessly leave us behind if we make the wrong platform commitment. Instead, we need to think of design simply as a discipline of synthesis. Be flexible on the tools and context.

Resist the container!

…and even the appearance of the container!

It was 18 years (this year, in fact) before Newfangled had a physical space that looked even remotely as beautiful or comfortable or stable as it should have. Not because we didn’t want nicer office space — nicer desks, nicer chairs, row after row of perfect, shiny mac workstations — of course we did. We’re only human! But there was always something else that we judged to be more important. To be more necessary. To be a better use of our time and resources. We never felt like we needed the perfect space to produce the right work. It’s always been about the work. Ask my colleagues. They’ll tell you about my Amish Dad tendencies and the crummy chair I sit in.

So don’t be seduced by those beautiful pictures on Instagram of that latest startups digs. The truth is, they probably won’t last. It’s the quiet ones that have their priorities straight. They’re off working, probably in some room that doesn’t look like much.

In other words, don’t mistake rewards for goals.

Learn to cooperate.

Entrepreneur used to mean someone who took on the full risk for an idea, including its funding. Today, entrepreneurs rarely do this. There is always someone else behind the scenes, and their name is probably on the checkbook. The unilateral, king of the mountain CEO ideal doesn’t really exist.

In the last year, I’ve had numerous conversations with people who have startup ambitions — big ideas — and seem to think there’s some magic to making that happen. Like some secret recipe that makes it possible for them to do it all alone. I’ll usually probe around a bit to figure out what this person’s strengths are, and then my first bit of advice is almost always to find a partner. That’s disappointing to most people, which I find strange and maybe even a bit troubling. What is it about collaborating with someone who brings strengths to areas where you are weak that is unappealing? Is it admitting that you have weaknesses? If that’s it, then you’ve got a big problem that will weigh you down for as long as you ignore it.

But more on ego in a moment.

Where I work, collaboration is essential. Mark O’Brien and I collaborate. He’s the CEO of Newfangled; I’m the COO. I don’t do what he does best as well as he does; he doesn’t do what I do best as well as I do. In the middle is plenty that we have in common — plenty of strengths, opinions, and perspectives — but it’s the differences that make our collaboration powerful. We’d be fools to think otherwise

Get comfortable with uncertainty.

You can’t control uncertainty. That’s why it’s called uncertainty! But you can control how you feel about it. Comfort can be a byproduct of success, but it’s not a great goal by itself. In fact, don’t underestimate the value of discomfort, adversity, uncertainty. They’re powerful motivators. If you felt comfortable all the time and certain of everything, there’d be nothing for you to do, would there?

Know yourself.

There is an independent agency in Cambridge run by a man I greatly admire. He’s one of those rare few that built it — slowly — from the ground up. But he learned that though he was able to build it on his own, he wasn’t going to keep it if he didn’t share the responsibility. He’s a wise man. In fact, he wrote a piece for Ad Age a few years ago that has really stuck with me. He was talking about how he has learned to empower the leadership at his firm — how to let them do their jobs to the best of their ability. He said he does this by making sure he has taken care of his ego at home. In other words, if he doesn’t have to satisfy his ego by micromanaging things, he can get out of the way and let the people he hired do the things he hired them to do.

We’ve all got an ego problem. It’s that we have one! The solution is not in denying your ego, it’s in taking care of it. If you don’t know yourself well, you’ll never figure out how to do that. Maybe that means making art at home. Maybe that means exercising. Maybe that means loving your kids. I don’t know. That’s up to you. But don’t expect to sustain success without figuring it out.

But there are two sides to the ego problem. Taking care of it in this way is about external damage control. But you’ve also got work to do to keep it from tearing you up inside. I think this should be pretty familiar territory for creative people especially. We’re an anxious bunch. We’ve got terribly high expectations. Those things set us up for disappointment and grief. So my last point.

Anxiety distorts time. Many of us are either living in the past or the future. That tends to produce behavior that is the result of “regret prevention protocols,” not being truly present — with what is true right now and those around us that make that true. So ask yourself, what sort of life do you want to lead? Not have lead, but lead. As in now. Remember, we’re stumbling along the path blindly. Taking satisfaction in the path, not where we imagine the path leads, is far more likely to produce the sort of success that you desire, that you’re hoping to look back upon someday.

Success is not about a label, or even about being a certain kind of person. It’s about being you. Truly you.

With that — with whatever you’re doing, or whatever you aspire to do — I wish you all great success.

Thanks for listening!