Before you read this article: This was written in 2013. A newer version exists, called Rethinking the Case Study, Again. Reading both is a great idea, but if you’re pressed for time, read the newer one. — CB

A Confession

We don’t have any great case studies on our site.

I mean that. But we have done great work. So what’s the problem here?

One obvious problem is time. Doing great work takes lots of time, which tends to not leave much left over to fill with writing about it. But everyone has that problem. The bottom line here: if it’s important, you make time. Writing case studies is important, so why haven’t we made the time? Well, it’s tough to make time to do something without having vision for it.

And that’s the other problem: vision. When I say “case study,” I’m sure you have an immediate idea of what I’m talking about. Prestigious client name emblazoned at the top of the page. Big, shiny images of that pretty stuff you made for them. Lovefest text about how cool you think your client is. Testimonial from them about how awesome you are. Followed, of course, by a halfhearted writeup of what you actually did. You were either in such a rush to publish it for publicity’s sake that you didn’t even bother to measure results, or so bored with it that you didn’t bother to frame it for SEO or promote it. Either way, the case study doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do.

No vision? No point.

Ok, so your vision problem may not be that bad. I know ours isn’t. You do great work. You even stick around to evaluate it, and are honest and humble enough to admit when it didn’t work. You dig in and fix it. But you don’t tell that story, do you?

Perhaps it’s simply a matter of not quite knowing how to make a case study as interesting and compelling as your usual thought leadership content. With that stuff, you can go all out on opinion; in a case study, opinion only matters if it gets results. So you don’t see a lot of that in typical case studies. And because of that, you don’t see many great case studies. You do see plenty of project writeups (like what we’ve got in our “Featured Projects” section), which are _fine_ (read: mediocre) but not great.

I saw something recently — something great — that has inspired me to change that. But more on that in a bit.

First, let’s build a new vision.

What Case Studies Are For

That idea we have of what a case study is — and perhaps I was being a bit harsh earlier — isn’t any good. But that’s not really because we don’t understand the elements of a case study. It’s because we don’t think clearly about why we are writing them in the first place.

Most of the time, we write a case study because we want the world to know that we landed an important account. It’s about the name of the client and what it means that they were willing to work with us. If we made some pretty things, we of course want to show them off too. But in both cases, we’re doing it to create an impression, either by name recognition or aesthetic seduction. And that’s what we think sells.

You might get someone into your store by putting pretty things in the window, but if that impression doesn’t hold up once they’re inside, they’re not going to stick around long enough to buy. Once they’re inside, they need all kinds of reassurance to defeat the voice in their head telling them to hold on to their money: A trust-building connection with you. The chance to hold that thing you’re selling and imagine what it might be like to own it. A good story about that thing that explains where it came from, why it’s one of a kind, and how it’s just as good as it looks. A promise that you’ll make it right if that thing doesn’t hold up.

Seduction is no more stable than a trap door held shut by twine. It’s going to fall out from under your prospect. What can you offer them in the way of a soft landing?

Better yet, why not skip the seduction altogether?

That’s what a good case study is for. It explains how you apply your expertise in the real world to potential customers that can relate to the problems you describe and understand the value of your solutions. It does this in detail — without seduction — covering:

- the kinds of problems you are good at solving

- how you probe and diagnose those problems

- your ideas for solutions

- how you test those solutions

- how you evaluate their performance

- how you execute the ones that hold up

- how you handle setbacks

- how you preserve forward momentum

- how you manage your relationships

A good case study does all of that because its purpose is to court prospects, not praise past work. It must differentiate you from the other options an informed evaluator is considering. And by the way, sometimes an option is a competitor, sometimes it’s the prospect themselves, sometimes it’s no one. You must make the case that paying you is a better investment than paying a competitor, doing the work in-house, or not doing it at all.

What a Great Case Study Looks Like

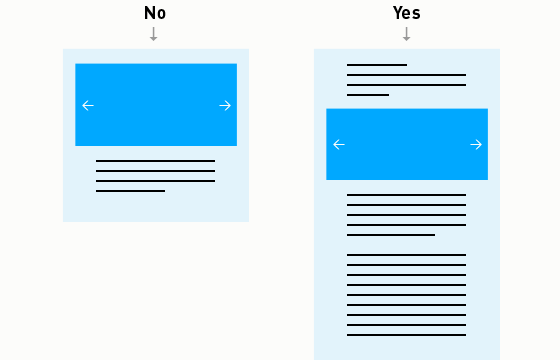

A great case study is substantial, and it’s going to look that way. Sure, it’s going to have a strong aesthetic component. But the curb appeal your case studies need comes from more than just pretty pictures. It comes from being well organized so that its depth is appealing, not daunting. Long-form content lives and dies by formatting. It either eases a reader in, or is an instant TL;DR.

I’ve long advocated for a predictable problem → solution → outcome format to case studies. I still think that holds up, but with the detail a great case study requires, that format is probably a bit too simple to be applied literally in every case. Instead, this is what I’ve come up with as a structure that covers those three concepts, adequately supports the more subtle goals we’ve been examining, and gradually guides the reader from big picture to granular detail:

- Summary: This is a brief introduction of the engagement, with an emphasis on problem and outcome. It should sell the reader on the value of digging further into the details of your solution. Think of it as an elevator pitch (if not something Tweetable). If a prospect only read your summary, would they at least understand what you did and the value you believe it offered?

- Backstory: Think of this as the beginning, the once-upon-a-time part. You’re setting up the case study by providing an introduction to its key players — you and your client — and your respective points of view. Remember, how you describe this relationship will make it easier or harder for a prospect to imagine themselves in a similar relationship with you.

- Problem: This is the simple part. What, exactly, were you hired to do? This hits on your expertise and your diagnostic and problem-solving skills.

- Solution: What did you do? This covers your process, your strategic prowess, your technical capabilities, your team dynamic, your style.

- Outcome: What were the results? Did you build a new audience? Strengthen and grow an existing one? Increase sales? Great. Data, please.

- Reflection: If a reader has stuck around to this point, you can trust them with a bit more vulnerability. Here’s where you share the insights and voices of individual team members — planners, designers, developers, even your client — through brief, focused reflections on the job. What worked? What didn’t? What doubts did you have? What surprised you? What would you have done differently had you more time or more knowledge at the beginning? What did you learn and how will you use that knowledge in the future? This, really, is the most important and substantial piece of the puzzle for a prospect. If they’re seriously evaluating, they’ve probably heard plenty in the problem → solution → outcome department, but your honest and sincere reflection upon it will be what helps them get to know you and want to work with you.

Remember, a case study is a sales tool.

Oh, and by the way, I’d recommend using a little editorial savvy here when it comes to titles. Unless your client’s name is so well known that the nature of their problem and your solution could be discerned by the sort of person you want as a client simply by hearing it, go for client-agnostic titles. Something like that describes what you did and the kind of client you did it for. Something like, “Launching a Worldwide Campaign to End Hunger,” rather than “We Worked With UNICEF.” The idea is to make the case study a mirror for your prospect. (If your client is that name-droppable, you probably don’t need to worry about writing case studies to attract prospects who don’t yet know you exist.)

A Practical Plan for Writing Great Case Studies

Writing a great case study sounds like a lot of work, doesn’t it? Even if we’ve got the vision problem worked out, time remains a significant obstruction. So what gives? As I confessed at the beginning of this article, we haven’t mastered this yet either. So, here’s what we’re planning to do:

First, we’re going to produce two types of case study. One will be the sort I’ve described here — I’ll call it the long-form case study — and the other will be a briefer format, similar to the case studies we’ve already published. The goal here is both to represent the depth of what we do, as well as to keep up with our actual productivity. Neither format can handle that alone; we need a combined strategy to best achieve our content goals. Here’s a breakdown of how each type will be produced:

Long-Form Case Study

- Frequency: Quarterly

- Length: 1,500 – 3,000 words (i.e. newsletter length)

- Target persona: Researcher, Evaluator

- Strategic focus: Aspirational; about the kinds of work we want to do more

Short-Form Case Study

- Frequency: Bi-Monthly

- Length: ~500 words

- Target persona: Evaluator, Buyer (remember some important personas will never read a very long case study, so the short ones remain important)

- Strategic focus: Representative; about the kinds of work we currently do routinely

That’s our current commitment: Up to ten case studies a year, four of which are of comparable heft to an article like this one, and the remaining six a much lighter effort. Altogether, potentially adding 15,000 words of expertise-focused, buying-cycle-friendly content. It’s ambitious, but we’re going to do our best to make it happen. We’ve got the vision, the plan, and the will to make the time we’ll need to do the work.

About that confession…

I don’t normally write articles like this. It’s risky. I’ve laid out a standard here that we have yet to meet ourselves, which I realize must sound a lot like the Dad who snarls “Don’t smoke!” just as he’s lighting up.

Actually, I wanted to avoid it ending like that. I wanted to end with something like, “Hey, remember that confession? Well, I lied. We do have one good case study on our site now, which I just wrote. Check it out…” That would have been great, but I’d have had to rush finishing the case study I am writing right now. It’s almost there, but not quite ready to accompany this piece. But I promise you, it’s coming soon. I’ve put my time where my mouth is and am hard at work trying to write a case study that comes close to being as good as it should be.

Update (03/10/2014): Since I wrote this, we’ve written three long, detailed case studies:

- We created a powerful marketing and benchmarking platform for middle market research with Rattleback and GE’s research group at Ohio State’s Fisher College of Business, The National Center for the Middle Market.

- We built an award-winning digital marketing platform for a leading outdoor sports marketing firm, Origin Design.

- We designed a beautiful new digital marketing platform for a major record label, Merge Records.

I mentioned earlier that I’d seen something recently that inspired this new approach. A few weeks ago I stumbled upon the website for Teehan+Lax, a digital agency in Toronto that has truly made an art of the long-form case study. In fact, their site is mostly just a collection of long, detailed, interesting, inspiring — great — case studies. Like this one, and this one, and this one. You should read them. But be warned: in addition to making use of all of the elements I’ve discussed so far, they are beautiful. Really, really beautiful. So beautiful that you might be tempted to think that it’s their design, not their content, that makes them great. You might even be thinking, Chris, after all of that hard talk about seduction, you send me here?! Well, I won’t deny that the visual presentation of these case studies makes a powerful impression, and certainly helps readers focus their attention enough to stay the course over a long read. But it’s the substance of these case studies that I want you to study. I wouldn’t want you to conclude that this sort of content is impossible for you to do just as well, simply because you can’t match Teehan+Lax’s design. (So you know: I’m intending to publish our case studies using the same template we’re using today, though I’d be lying if I said I wouldn’t love to create something just as custom as they have.)

If you’re motivated to make case studies a core platform of your content marketing, I recommend you become a student of their website just as I have.