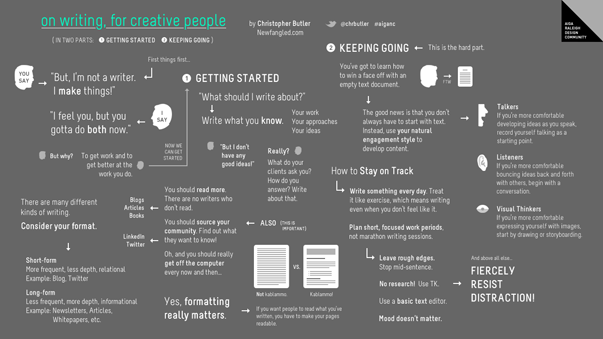

Too small? This image comes in a larger version or in a downloadable, print-friendly PDF version.

Also, no, this is not a good infographic. Just so we’re all clear on that.

Today I had the pleasure of speaking to the Raleigh AIGA about writing. Thanks so much to Laura Hamlyn, Maura McDonald, and Matthew Munoz for making this event happen! Rather than present with a traditional slide deck, I gradually built the image you see above as I talked to the group.

Ugh, Do I have to? Ok, call me Hemingway.

I began by anticipating an argument over whether designers should write:

Frustrated designer: “But, I’m not a writer. I make things!”

Me: “I feel you, but you gotta do both now.”

Honestly, I don’t actually hear this argument much. But, I’m surprised I don’t. As a RISD student (over a decade ago), I was required to take a certain number of liberal arts credits (not many), but it was abundantly clear that, to students and administrators alike, studio courses were the priority. And as far as I could recall, writing—in any form, whether that be papers for classes or even artist statements—was wildly unpopular. I took several writing-heavy courses. They were all poorly attended. It was very typical to hear my classmates complaining about any writing requirement, no matter how brief: “What’s the point of writing papers? We’re going to be designers!”

Ten years later, designers are doing a lot of writing and, as it turns out, not much complaining. In fact, where I thought I’d hear bellyaching, I instead hear boasting. (And when I say “hear” I really mean, appropriately, “read.”) On the internet, writing is held in very high esteem. I follow many designers on Twitter, for example, where the majority of them describe themselves as writers—often before they even mention design! Something like this is pretty common: “I’m a Writer, Speaker, and Designer working at…” Somewhere along the line, writing came in to fashion big time, so much so that it pushed design down to the bottom of the job description. (I won’t even get into the public speaking thing.)

This is ultimately the result of technology. Specifically, in three flavors: First, the availability and affordability of production tools has made “professional” quality output within reach of more people, which raises the bar of expectations. It’s harder to impress people with images alone. Second, the internet has made geography irrelevant; American designers with higher overhead now have to compete with designers overseas who can do the same work for less. It’s harder to get clients and earn what you need to earn. Third, search engines. If a potential client you don’t yet know about is going to pick you out of the crowd, this is probably where they’re going to start. But, if you haven’t produced any words, you’re practically invisible to a searcher. Sure, you can still get somewhere by good old-fashioned networking, but as soon as a potential client has your name, they’re going to Google you. Better they find something to help them vet you rather than nothing.

In a world where search relies upon semantics, writing has become the means by which we must differentiate ourselves from everyone else. It’s become how we demonstrate our expertise—by describing it, not just showing it. That’s been a huge shift, especially for creative professionals. It’s no longer enough to have a beautiful portfolio.

But even if none of that was true, I believe that writing about what we do makes us better at doing it. It’s a means by which we can work out our thinking, explore ideas, and gain feedback before we make things, while we’re making them, and after we’ve made them. Writing is good for design.

(Oh, and if you’re a “blogging is dead” type, see here.)

What Should I Write About?

For the convinced, the first big question is, “What should I write about?” The easy answer is to write what you know. But for many designers, that’s still pretty broad. I don’t mean anything you know, but specifically, what you know related to what you do: Your work, your approach, your ideas. Try it in that order, too. Start with describing things you’ve already done. Outline the challenges, your solutions, and then the results. That case-study approach, assuming you’re actively producing new work, should be relatively easy to sustain. But then you can go deeper. Describe your philosophy—how you approach your work in general—and why that makes you or your work different. Especially if you’re uniquely positioned (“I specialize in _____ design for _____” rather than “I’ll do whatever for whomever”), content articulating who you are, what you do, and for whom you do it, is essential. Lastly, talk about your ideas. Even far-out-there ideas can have a place—in blog posts, for example—among the more practical content that is likely to generate interest. In fact, you may even be hired some day because of your wilder ideas.

“But I Don’t Have Any Good Ideas!”

A common response to this is worry over what happens when you run out of ideas (or, even if you have no good ones to begin with). We designers are an anxious bunch. We’re always worrying about negative outcomes. My answer to this is in two parts. First, we’ve got to stop obsessing over the “big idea.” This is contrary to culture (TED, for example), but big ideas aren’t the only thing that make the world better. Some big ideas are at their most glorious on stage, but get much smaller when they step down, into the real world. The real world runs on small ideas, mostly borrowed and shared, by the way. If you’ve got an idea, no matter how small or stale your critical inner voice thinks it may be, there’s no harm in writing it down. Especially if there’s someone out there who could benefit from it. And that brings me to my second answer. Think about your client interactions. They’re probably frequent (at least every day) and typically Q&A sessions. I’d bet you are asked some questions over and over again. That’s content, right there. But it’s difficult to remember that when you sit down to write. So, next time you’re on the phone or in a meeting with your client, take note—literally, write them down—of the questions they ask you. Each one could be a blog post.

There is no good writing without reading.

This is a pretty straightforward principle, I think. I just really don’t believe you can write well without being very familiar with the written word. Books, articles, blogs, whatever. You should be reading more than you write. That fills your mind with a rich diversity of ideas and voices and, working together with regular and active writing on your part, will help you to find your own voice.

Source your community.

If you still aren’t sure of what to write, or maybe just how to approach a subject, ask for help. Both LinkedIn—in their Answers tool as well as their groups—and Twitter offer really powerful ways to find out what your community thinks about things or what they want to know more about. When in doubt, just get out there and ask.

Go Offline

Also, it doesn’t hurt to get off the computer now and then and do something physical. That involves a different kind of thinking, one which is sure to enrich whatever you do online. Here’s a great offline exercise for prompting creative thinking you might try.

What about format?

This is actually not a very common question, but it should be. I often run into the assumption that designers should blog, but that’s not always a given. Rather than think too much about the technical format—”blog” vs. something else—I think it’s best to consider two general formats: short-form and long-form writing.

Short-Form

Short-form content—which could take the form of a blog or even a Twitter account—takes a cumulative approach to telling the story of your thinking through many shorter, less formal posts. When people subscribe to this content, they are entering into a more intimate form of relationship with an author, more so than with other platforms, which tend to attract topical interest. But with a blog or twitter stream, it’s not just about the information itself. The point of view and the author’s voice, often delivered in a more casual, raw and almost improvised manner, are just as important to building and maintaining readership. Because this format is generally more casual, brief (~500 words), and frequent than long-form writing, which I’ll get into in a moment, it’s also one that allows for more risk. Not every idea you discuss in a blog or tweet needs to be road tested, backed up with data, or what have you.

With short-form writing, there’s value in remaining top-of-mind for your readers, so that of course implies a certain level of frequency. I generally recommend finding a comfortable volume somewhere between once a week and every weekday. There are blogs I read that stick to a once-per-week schedule and deliver a rich, thought-provoking piece that I can expect and will set aside time to digest. There are also a few blogs that publish every single day. It’s usually lighter material, but it’s a stream of thought that comes naturally to the writer, one I’ve decided to tap into. But most blogs are somewhere in between. As I’ve said, short-form writing is generally informal, which means that the more of it you produce, the easier it will become. You should get to the point of writing as fluidly as you would speak. But no matter what frequency you settle upon, consistency is more important than volume.

Regular editorial planning sessions, in which you plan specific topics, will probably be necessary to keep you producing, though at the outset you may have enough excitement and momentum to make planning seem unnecessary. Stick with it, though. Over time, there will be dry spells where the system will be the only thing between you and an apparently abandoned blog.

Long-Form

Long-form content—which could take the form of newsletters, articles, whitepapers, or case studies—routinely develop a single-idea important to your expertise and positioning in one, focused piece of writing. Compared with a blog post, for example, a long-form piece is generally going to be more formal as well as substantially longer. 1200-2500 words is a reasonable range; it can be more—though your audience will shrink as the length increases—and probably shouldn’t be less. I tend to describe long-form writing as regular opportunities to go “on the record” on a subject critical to what you do, so editorial planning is even more critical to this platform.

Because of their length and formality, long-form writing will naturally require considerably more work (time and research) to produce. With that in mind—and the same principle of consistency over volume as I mentioned for blogging—publishing monthly is probably as far as you’ll want to push it. If you don’t think you can consistently meet a monthly deadline, start at once every other month or quarterly and assess that schedule after you’ve maintained it for a year. For things like case studies and whitepapers, the publishing schedule should be based entirely upon relevance—when there is a new project or approach to discuss—than an arbitrary production routine.

How to Win a Face-off with an Empty Text Document

Everything I’ve written so far is preliminary to actually getting started—the hardest part, unfortunately—which often takes the form of a face-off with an empty text document. And which we often lose. We need to learn how to win.

The best way to do that is to figure out what your natural engagement style is. What I mean by natural engagement style is the way you naturally engage with ideas. For many people, that isn’t a written experience. This is especially true for those working in the “creative” fields. For us, visual engagement is much more natural. No wonder we have such a hard time with writing! So the good news is that you don’t always have to start with text.

To identify your natural engagement style, think back to your last “aha!” moment—the last time something really clicked for you, or when several threads came together in your mind in an important way. For some people, this happens when they’re explaining something to someone else—it’s by verbalizing their ideas that they realize them for themselves. For others, it happens in conversation, relying upon the immediate input of others to bend and shape ideas into something new or resonant. And for others, it’s classically visual. Whether by sketching, drawing, or even building models, some people’s thoughts find a much more natural voice in images or objects. The trick is in figuring out where (or whether) you fall in these categories and learning to harness those unique starting points better.

Talkers

If you’re more comfortable developing ideas as you speak, start with speaking! Use your computer to record yourself talking—either with video too or just audio—and either transcribe that material and use it as a starting place for a written piece, or maybe just publish it as-is from time to time, especially as you get comfortable with the recording. Here’s an example of what that might look like.

Listeners

If you’re more comfortable developing ideas in conversation, then start with a conversation! Grab a friend or colleague and sit down for a chat in order to bounce ideas back and forth. You can record that conversation and, again, transcribe it as a starting place for an article, or even just publish the recording (assuming your chat partner is OK with that). Here’s an example of how a great conversation can be turned into a blog post.

Visual Thinkers

Or, you may be more comfortable expressing yourself with images. In that case, start by drawing or storyboarding your ideas and use those sketches as a starting point for an article. Some people might even occasionally stick with the storyboard itself. There’s no reason that some of your content couldn’t look more like a comic book than prose. A great example of this are the sketchnotes that several designers have been creating to report on conferences like South by Southwest.

If you’re actively writing, you’ll probably find yourself using all of these methods (see here for example). But if you’re the kind of person that needs to start with the text doc (not that there’s anything wrong with that!), these strategies won’t be as helpful as some of the things I want to share about how to stay on track once you get going with writing. So, on to that…

Tips for Sustaining Writing (and Not Burning Out After Writing Just One Epic Thing)

Writing something is an isolated event. If that’s all you’re going for, I suppose you could just hole up for a day and bang it out. That is, after all, what many people think writing looks like. But if you want to repeat that on a regular basis—I mean actually make writing a part of your life, rather than just write something once—then you’re going to have to take a very different approach. Writing is a lifestyle that requires intentional upkeep.

“Write every day.”

I’m sure you’ve heard this one before. Me too. I always assumed it meant that if you were, say, writing a book, the way to do that well is to work on it every day. But, I’ve come to a different interpretation: If you want to write well, you have to write something every day. Last year, I wrote a book called The Strategic Web Designer (it’s coming out this summer from HOW Books). I started out by trying to apply that first interpretation—by attempting to work on the book every day. That worked for about one month. I was excited about the project, and that was enough to motivate and sustain me. But then I hit a wall. It wasn’t writer’s block; it was, instead, demand. See, the book project I took on was on top of other things I still had to do, and not just the day-to-day stuff I do at Newfangled, but also other writing: I write a monthly article for Newfangled that is, on average, about 2600 words. Getting that written and published is a non-negotiable for me and can’t be sidelined while the book is in process. I also try to blog regularly—something that can slow down a bit, but not stop completely—here at Newfangled and a bit on my personal site. On top of that, I’m a regular contributor to PRINT Magazine (and their blog), HOW Interactive Design, and write occasionally for Smashing Magazine. Between the book, Newfangled’s newsletter, blogging, and contributing articles to other publications, I’m trying to manage and sustain 4 different kinds of writing at the same time—in addition to my regular duties at Newfangled. It is not easy.

So, there I was early last year, struggling to find the time and motivation to focus on my book. I felt discouraged that I couldn’t maintain this writing every day thing. I felt disappointed that I couldn’t be as disciplined as I wanted to be. I felt like a failure. I went on feeling this way for most of a month, even as I managed to produce another chapter, write a newsletter on prototyping, 8 blog posts here, 3 over at my personal site, 3 at Imprint, and my first column at PRINT. So, what gives? In retrospect, it seems like a lot of output, so why was I feeling like a slug? Toward the end of that month or so, I got hit with some inspiration. I had read an inspiring post about blogging and then watched an even more inspiring miniseries about art and design. Within a week I had written 6 new posts on my personal blog—a series on “Seeing Time”—which, as far as I can tell, nobody read. But that’s ok. I was having fun and feeling good about writing. Meanwhile, I also wrote two more chapters of my book. That’s when it hit me. I was writing every day. I no longer felt like a slug. It was working.

Writing every day is to writing what stretching is to exercise. I didn’t have to be working on my book every day to reap the benefits of regular writing. That’s why it’s like stretching. I’m a regular exerciser, and I’m not nearly a regular enough stretcher (trying to get better), so this is one of those do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do kinds of things. So, that said, stretching enables your body to do the heavy lifting in your exercise regimen without injury. It maintains flexibility. Otherwise, your muscles remain tensed and more vulnerable to tearing. Writing, in a way, is like that: If you don’t loosen up by writing every day, you will burn out by doing these intense bouts of “heavy lifting.” Writing burnout is similar to an exercising injury—it puts you on the sidelines and steadily reduces the motivation to get back in the game.

Outside of the metaphor, regular writing breaks down the barriers between your mind and the written word. It helps you to more quickly and confidently express your thoughts through words, and reduces those recurring type-delete cycles you’ve probably been frustrated by when struggling to just get a sentence out.

OK, that was the longest one. The rest are very straightforward, I promise.

Mood doesn’t matter.

Really, it doesn’t. I wish it did, really. Things would be so much nicer that way. But the reality is that you’ll need to be able to write in all kinds of settings: at your desk, in the middle of the day, at home, at a coffee shop, etc. These settings may change, so pay attention to where you’re productive. But forget any romantic notions of special writing rooms with aromatherapy and what not. Mood doesn’t make the writing happen, you do.

Write for short, focused periods.

I’ve found that I’m much more productive if I give myself 30 minutes to 1 hour to write and no more, rather than clearing out an entire morning or more to write until I finish. Instead, I’ll set a time, disconnect from the internet, and write for only that time. It’s amazing what you can get done in a half an hour.

Leave rough edges.

This one works pretty well if you’re doing the focused writing sessions thing. When your allotted time runs out, stop writing. Even if you’re midway through a sentence. That gives you something very concrete to dig in to in your next scheduled writing session. Since your thought was left unfinished, you’ll also have to review a bit and perhaps rethink some of what you did before. That’s a good thing.

Use a basic text editor.

You really don’t need to format anything until you’ve already written it. Until then, formatting is a distraction.

And above all else, fiercely resist distraction!

Close your browser. Close your email. Close your instant messaging. Close Skype. Close Twitter. Turn off your mobile phone. Whatever you have to do.

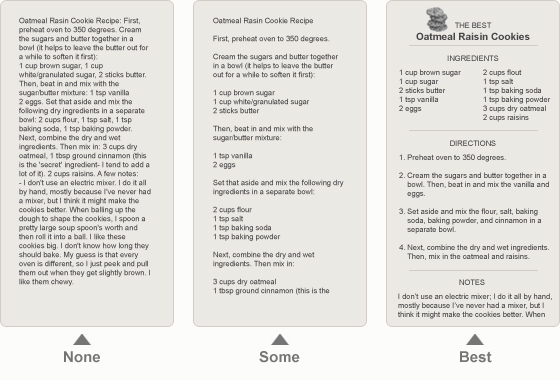

Now, here’s where looks matter.

How a piece of writing is formatted is incredibly important—I don’t want to underestimate that—but until that piece of writing exists in its final state, formatting should be the last thing on your mind. Otherwise, it will distract you and probably compromise the quality of your writing. So, after you’ve written something, after you’ve had it edited, after you’ve had it proofread, then you can start making it look pretty.

A couple of years ago, I wrote one of our newsletters on blogging and included a section on formatting your blog posts. My main point was to dispel the notion that “If you write it, they will read.” There is just too much content (and too little time) for any of us to expect that what we write will capture the attention of readers without a little extra work. In preparation for that article, I asked a question on LinkedIn to confirm what I suspected was going to be the case: the format of an article—its length, title, how the text is laid out, and the use of images—is just as likely to determine whether people actually read it as are good ideas and quality writing.

Anything you write is competing for attention with about a billion other articles on the web. The impression your article makes on a reader in that incredibly brief moment in which she decides whether or not to stick around and read is almost completely dependent upon it’s format. And that happens in just ten seconds. Can the reader quickly scan the article and figure out whether its relevant enough to actually read? If you’ve got a title and a single block of text, probably not. That extra bit of work I mentioned above involves breaking up your article so that it is easy to scan—thanks to headlines, sub-headlines, lists, and images—and easy to read—thanks to good typography and shorter paragraphs. These things will give your page the visual structure it needs in order for a reader to make an informed decision as to whether to stay or go.

Put simply, design is the difference between a bounce and a conversion. Thankfully, design is what you do best!

With that, I’ll wrap it up. There’s a lot here to dig into further (and I hope you do), but believe me: If I can do it, so can you. Let me know if I can help in any way.