Yesterday, the entire Newfangled team gathered for a one-day mini-retreat. This is something we do each winter as a sort of state-of-the-company event, where we go over company news, talk about various topics related to what we do as a group and individually, and think about where we’re headed.

As part of that event, I gave a brief presentation on the notion of hyperity–that we’re in a state of being connected all the time, and everywhere–and how that affects and will affect our company. Below are some of the key slides and an explanation beneath…

Hyperity

After a particularly intense work week recently, I remember coming coming home and thinking the word “insanity” over and over again in my mind. I was frustrated by what seemed to be a generally accepted expectation that we all be connected and available all the time, and receptive to unceasing input–emails, instant messages, phone calls, text messages, alerts, etc. I think I had just hit my threshhold for it all, and as I repeatedly thought the word “insanity,” it began to morph a bit–insanity, humanity, hyperhumanity, hyperity…

I checked the entry for hyper on Wikipedia to make sure this made sense. According to their entry, “the prefix hyper- (comes from the Greek prefix “υπερ-” and means “over” or “beyond”) signifies the overcoming of the old linear constraints of written text.” Seems pretty suitable for my new word, meaning “the state of being over connected, all the time, everywhere.”

The Future is Technology People People Making Wise Decisions About Technology

Whether we like it or not, hyperity is the way of now. It’s how most people are operating, and how most people expect others to operate. I won’t get bogged down with dealing with the right and wrong of it–I think this is covered pretty extensively in the brief post I wrote about human enslavement to technology and the wonderful conversation that’s emerging in the comments string–but our response to it is worth talking about a bit.

In a company like ours, it can be very easy to assume that our future will be determined by technology in general. Often, this means a larger technological shift–perhaps coding standards, a new device, etc.–that will either reinforce our value or render us obsolete. But we’ve already been in business for 15 years, through many shifts of this kind. The defining characteristic is not technology, nor is it just people. People have come and gone during that time. The more important measure of our resilience has been and will continue to be the choices we make in regard to technology.

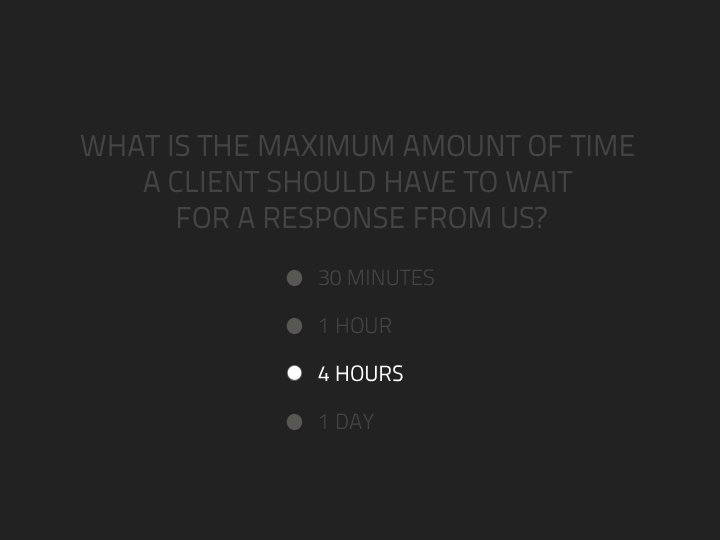

I wanted to briefly step back for a moment and ask our team a question: “What is the maximum amount of time a client should have to wait for a response from us?” We actually have a company-wide policy on response time. I made this a multiple choice question because I suspected that most people who interface with our clients have shifted to thinking that their response time should be much faster than we originally determined was best. As I suspected, many people did, choosing “30 minutes,” or “1 hour” as the answer. In fact, our policy has been that 4 hours (or half a day) is a reasonable amount of time to wait for a response to a request, provided it’s not a legitimate emergency. Having a policy like this is really meant to serve our clients well. Rushing to respond can actually encourage sloppier work as often the request may require a bit of inquiry before it can be responded to. The disparity here between how people are really operating and our policy is an indicator that hyperity is the way of now.

The Boomerang Effect

Consider this scenario: At the end of the day–perhaps you’ve just eaten dinner and find yourself between activities–you decide to check your work email. You find a few messages that arrived after you left the office. Immediately, your pulse quickens a bit. You want to reply to those messages now, while the info is a bit fresher in your mind, and mostly in the hope that you’ll come in the next morning to a clean slate with no leftover work from yesteray. So you quickly scan the emails and fire off responses. You sign off and shut your laptop with satisfaction. Meanwhile, though, your client or coworker is off somewhere, perhaps at dinner or a movie with their spouse, and feels their blackberry buzz in their pocket. Immediately, their pulse quickens a bit. They want to reply to whatever new message has come in now, for the same reasons you did. They excuse themselves (I’m assuming politeness here, but come one, we’ve all seen people gazing at their pocket screens at dinner) and quickly scan the message and fire back a response. They pocket their blackberry again and return to dinner satisfied.

You can see where this is going. It’s a cycle that could repeat several times before either person really “calls it a night.” But the key point here is one of motivation. In both cases, each person is more motivated to deal with the input quantitatively–process the email, redirect it, clear the inbox–rather than qualitatively–really engaging with the content of the message. As a result, the quality of each reply degrades with every boomerang cycle.

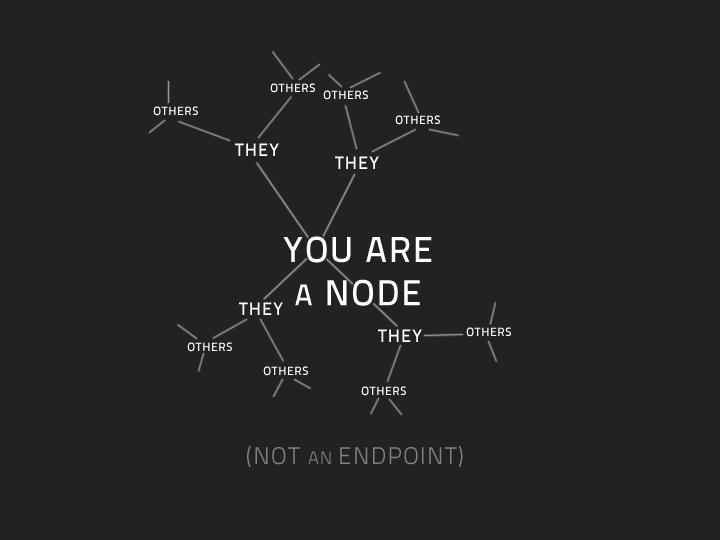

You Are a Node, Not an Endpoint

My sense is that the boomerang effect results from us seeing ourselves as endpoints in a communication cycle. We tend to think of it as strictly linear system in which we either receive or send out input. But what really happens when we receive input is that we often have to parse it out among multiple other recipients. For a project manager, for example, any input they receive from a client is often relevant to several other people on a production team–the designer, the developer, the resourcer–not just the project manager. When we’re motivated to simply clear our inbox, we are overly simplifying the system we’re actually in, which is a complex one of many nodes. We’re just one node in that system. The only way to end the boomerang effect, which, remember, quickly degrades quality, is to be a steward of the other people in the system, and of the system itself. If you care about quality, and you care about your own peace of mind during off hours, delaying a response could serve you much better than hastily replying and creating more work for others.

“Interruptions are the enemy of work.” – Jason Fried

This quote comes from a video of 37 Signals co-founder Jason Fried. He’s got a serious point, especially for production, but for organizers (managers, project managers, etc.), managing interruptions is a way of life. Somebody has to do it. Of course, regardless of the role you occupy, the idea that distractions can actually cause a drop in IQ should be a sobering one. As Dave pointed out to me yesterday, seeing this idea in graph form is even more effective.

The Plight of the Organizer/The Plight of the Producer

Most of the time, doing their job well requires organizers to do some of somebody else’s job as well. This happens all the time with managing project timelines. The project manager representing the production side of a project (like our company) will keep the client aware of key dates and what is needed from them to hit deadlines. However, the client often does not take ownership of the timeline, assuming that the organizer will continue to send reminder after reminder until someone decides to take it seriously. If this doesn’t happen and a deadline is missed because the client fails to deliver something, it’s the production teams’s organizer that takes the heat. “Why didn’t you tell me we were going to miss the deadline?!?!” So, we have an internal mantra for this:

“Your client must hear from you more than you hear from them.”

This works very well, but it has definitely contributed to the organizer measuring success by processing every input they receive as fast as possible. Keeping things moving is the priority.

On the other hand, most of the time, being available to receive unscheduled input from the organizer compromises the producer’s (designer/developer) ability to do their job well. Our solution to this has been a thorough resourcing system, and a schedule based upon benchmarks. And this works very, very well. We deliver projects on schedule, under budget, at a very high level of quality. But, it has also resulted in squeezing the freedom to think and contribute in a human way from the producer’s day. They desire to deliver their work at a higher level of quality than the system may allow.

This is our goal. Simple. Good for everyone. But does our process support this goal?

Examining the “plights” of the organizers and producers, it seems that each measures success in a way that ultimately compromises the other. As we’ve already seen, it can be very easy to reframe good organizing simply in terms of the speed with which we process input. With the boomerang effect, everyone’s thinking and responses are not as good as they could have been if speed wasn’t the priority. The more we act based upon our desire to simply reduce inputs, the more inputs we’ll actually receive. We must control the pace. Meanwhile, the relationship between quality and input is just as true for the producer. They need the latitude to really focus on their work without distractions in order to deliver it at the quality they are capable of. Both groups need the other to succeed, and, at least at our company, truly want each other to be successful.

Here’s where this gets interesting. I think I’ve properly diagnosed the situation (and it should be said that this is not an emergency, but addressing this will be what enables us to continue to grow and improve as a company, reaching our full potential rather than remaining static), but I don’t have a complete solution. However, I do think we have to begin symbolically. First and foremost, we are one team. We’ve had lots of different language (depending upon who you talk to) over the years indicative of divisions, like “business vs. tech,” “front-of-the-house vs. back-of-the-house,” or “us vs. them.” That’s all in the past. We’ve even moved everyone in the North Carolina office–project managers, developers, engineers, etc.–into one room to further empasize how we actually want to work and communicate.

Above and beyond that, the culture we need to continue to build and maintain won’t be accomplished by technology or systems alone, but some systems could get in the way. Where that is true, we need to fix quickly.

My next step is one of observation, so I’m very interested in any opinions, feedback, complaints, whatever to help me navigate this.