In my last post, I talked about how you can figure out what’s really going on with the bounce rate for specific pages on your site. But bounce rate isn’t the only indicator of a page’s value; there are other factors that provide just as much insight into its overall health. In this post, I’ll look at two of those beyond-bounce-rate metrics: exit rate and time on page. The key difference here is that, unlike bounce rate, these metrics are not equally useful for all types of pages; you’ll need to decide case-by-case how much they matter for each individual piece of content. Here are some thoughts on when exit rate and time on page matter and how to look at them.

Exit Rate

OK, so here’s why exit rate is more ambiguous than bounce rate. No one *has* to bounce from the site, ie, leave after viewing just one page—so your site has an overall bounce rate, and it makes sense to work on lowering it. Exit rate is different because everybody *does* have to exit at some point—over time, your site’s overall exit rate is effectively 100%. So if you lower the exit rate for one page, those exits will just happen somewhere else, and the rate will go up there instead.

That said, there are some pages that are more logical exit points than others. For instance, the confirmation screen from your shopping process: if someone makes it through the checkout, successfully orders a product, and then leaves, that’s probably OK. Sure, you can encourage people to keep shopping and hopefully some will, but overall, people who make it to the confirmation page have accomplished what they needed to on your site. On the other hand, if large numbers of people are bailing at step 1 of a three-step checkout, then there’s a problem. Other places where a high exit rate could indicate a problem: page 1 of a 5-page newsletter. Or a search results page: if people are doing searches and then leaving without clicking on any of the results, it might mean they’re having trouble finding what they’re looking for. (If that’s the case for your site, check out Brian’s series on tracking internal site search, for ideas on how to get more information about the issue and what to do about it.)

So compared to bounce rate, it takes a little more thought to evaluate whether a page’s exit rate is good or bad—in some cases, it might not be either. The general questions to think about are, does this page have a specific mission to deliver people to other content, and if so, is that happening or are they leaving? Although you can always direct people on to another page, if that’s not the main purpose of the page you’re evaluating, the exit rate might not be the most important indicator of value.

Time On Page

This is another one where the raw number has to be evaluated case-by-case before you can really say if it’s good or bad. The knee-jerk reaction is that of course more time on the page is better (after all, Google Analytics lists increased times in green, and green means good!). But again, whether more time is really better depends on the purpose of the specific page you’re looking at. A distinction Janice Redish makes in her web writing book Letting Go of the Words is useful here: as Redish explains (starting on page 53), there are some pages that are pathway pages, and there are others that are information pages. A pathway page is one where the user’s purpose is to “scan, select, and move on”; the information page is the one they’re trying to get to, where they’ll actually stop and read a little bit. If people are hanging out on a pathway page too long, it could mean that they’re having trouble getting to the information they’re looking for—in that case, extensive time on the page may actually mean people are confused instead of engaged.

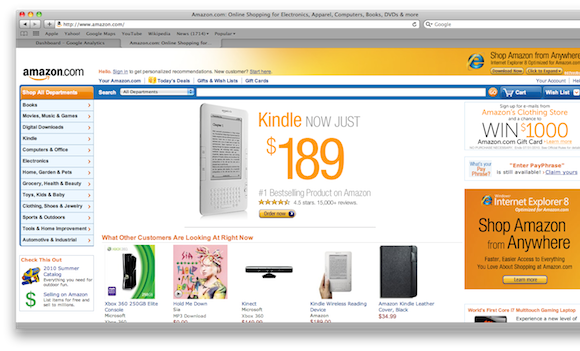

You can see the difference in practice by thinking about the shopping experience on Amazon. If you start out on their homepage, Amazon is providing you with a lot of ways to get into the site—you can search, choose a department, or go straight to one of the recommended products they’re featuring. What you’re not meant to do is just hang out on the homepage—if you’re doing that, it means a) that you’re not buying something yet, and b) that you may be having trouble figuring out what to do. In this case, spending less time on the homepage probably means that you’re having an easier time using it.

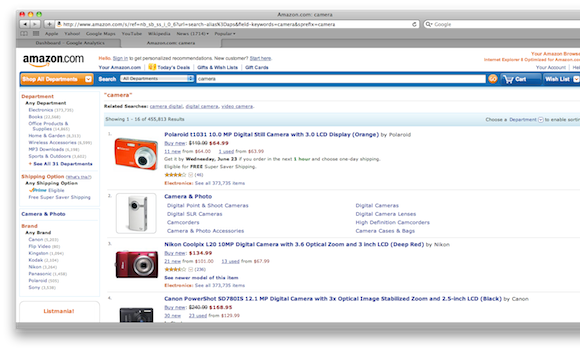

Same thing once you do a search—you get a list of products, you scan it, and if something looks like what you want, you click on it. You’ll probably take some time on the list page to start doing mental comparisons, but not too much time. In general, the easier Amazon has made their results list to scan, and the better that list matches what you’re looking for, the less time it will take you to find and click through to a product.

The product page is where you’re going to slow down and spend some time, and here there’s plenty to see and do: additional images, product details, user reviews, etc. Here’s where more time on the page probably really is better: if you’re spending some time, you may actually be considering the product you’re looking at.

Photos, specs, alternatives, reviews…there’s a lot on this product page that you could spend a lot of time digging into.

So again, the value of a page’s average time spent will depend on that page’s purpose. For a lot of content pages, more time spent can indeed indicate that it’s doing well; if people spend an average of 3 minutes on this blog post, it will probably mean that they’re finding it more valuable than if the average time is 10 seconds (just long enough to decide they don’t want to read it after all). On the main blog list page, the meaning of time spent is more neutral. Someone who spends several minutes there isn’t bailing, and they might be thoughtfully reading the abstracts and considering what to read next, but it may also mean that nothing is really grabbing their attention. For that page, time may not be the best indicator one way or another.

There’s Always More

These still aren’t the only ways you can assess a page’s performance. It all goes back to what you’re trying to do with that page. Is a campaign aiming to reach people who haven’t heard of you yet? Maybe the percentage of new visitors is what to start out with. Conversely, want people coming back to your blog over and over? In that case, visitor loyalty may be key. Thinking about your content this way takes a lot of work—much more than scanning a list of bounce rates and pronouncing yea or nay. But it’s a really good exercise to go through, and is likely to benefit your site as a whole. After all, if you can’t identify some aim for a given page, it probably shouldn’t be there in the first place. Once you’ve identified the goals, you can choose the metrics that best show whether you’re hitting them.