I recently finished reading Kevin Kelly’s latest book, What Technology Wants, and have since been reflecting upon his point of view on what technology is and how it shapes our culture. There’s a ton of material available on the book at this point, most of which covers the central idea that technology is so interwoven or embedded into human existence that it’s progression towards the future is almost deterministic. Kelly’s title comes from the idea that technology has “wants,” or demands its current existence makes on us.

[Aside from reading the book itself—which I recommend—there are a few good sources that can give you a primer—a WIRED magazine sponsored dialogue between Kelly and Steven Johnson, a review from the Technology Liberation Front, and another not-so-positive review from the New York Times. Kelly himself has posted a long list of reviews and mentions on his website.]

No Learning Without Grandparents

But one idea that has stayed with me since the beginning of the book is something that Kelly mentions as he describes the slow progress of human civilization early in the book. He writes (it’s a long quote so I’ve set the most critical piece in bold):

“A typical tribe of hunters-gathers had few very young children and no old people. This demographic may explain a common impression visitors had upon meeting intact historical hunter-gatherer tribes. They would remark that ‘everyone looked extremely healthy and robust.’ That’s in part because most everyone was in the prime of life, between 15 and 35. We might have the same reaction visiting a trendy urban neighborhood with the same youthful demographic. Tribal life was a lifestyle for and of young adults.

A major effect of this short forager life span was the crippling absence of grandparents. Given that women would only start bearing children at 17 or so and die by their thirties, it would be common for children to lose their parents before the children were teenagers. A short life span is rotten for the individual. But a short life span is also extremely detrimental for a society as well. Without grandparents, it becomes exceedingly difficult to transmit knowledge—and knowledge of tool using—over time. Grandparents are the conduits of culture, and without them culture stagnates.

Imagine a society that not only lacked grandparents but also lacked language—as the pre-Sapiens did. How would learning be transmitted over generations? Your own parents would die before you were an adult, and in any case, they would not communicate to you anything beyond what they could show you while you were immature. You would certainly not learn anything from anyone outside your immediate circle of peers. Innovation and cultural learning would cease to flow.”

While this kind of anthropological evolutionary reflection isn’t exactly new (there are plenty of good, popular books in that vein, like Guns, Germs and Steel and Pandora’s Seed), I found Kelly’s point, in that it supported a reading of technology and humanity’s symbiotic relationship, compelling. If the point seems soft when considering a small tribe with the family structure we know today (I actually think that without Kelly’s point, we’d probably think of it that way anyhow), consider what today’s society would look like without grandparents. The difference would be radical.

The second time I read Kelly’s passage, I thought about my earliest memories. I’m not certain of the exact sequence—which are actually oldest, I mean—but most of them involve my Grandparents. In fact, I have a memory of walking/crawling up a grassy hill toward the retirement home that my Great-Grandmother spent her last few years living with my mother and Grandmother, which must have been when I was around three years old. I have more vague memories from before that, which also involve my grandparents. But afterward, much of my childhood was shaped by them, as they lived nearby and I and my sister spent most afternoons after school with them until my mother came home from work. They taught me many things—not only deeper, life-lesson type things, but also practical things like cooking, cleaning techniques, how to do laundry, and how to make my bed. Those things shouldn’t be downplayed; just because most of us know how to make a bed doesn’t mean we didn’t have to learn it from someone. Anyway, I can’t imagine a life in which they didn’t exist, nor can I easily imagine society without people like them.

No Learning Without Childhood

Then, just the other day, I heard a quote from Jaron Lanier, author of You Are Not A Gadget, in an interview with Anne Strainchamps on WPR’s To the Best of Our Knowledge. Like Kelly, Lanier is a technologist who has done a lot of thinking about the relationship between humans and technology, and in particular, how evolutionary twists and turns have contributed to how we and other species operate. But more interestingly, and also like Kelly, Lanier has concluded that a particular life stage—in his case, childhood—has been a necessary component of our development and progress. He says (again, I’ve bolded the essential parts):

“There could be a future in which communication between people becomes incredibly more rich and intense than what we’ve known so far. Now, as it happens, evolution on Earth is awfully creative and she’s come up with a creature that can do some of that. So, some of the cephalopods—some of the cuttle fish and octopus—can morph. They can just, at will, project images on their bodies and change their shape and turn in to different things. It’s just the wildest thing and they do great stuff with it. For instance, there’s a cuttlefish that hunts for armored crabs and it’s just this soft little thing. They’re kind of like people in that they’re soft creatures that have to live by their wits instead of by their brawn and the way they hunt is by psychadelic art. They turn into these weird morphing displays that just totally stun the crab. So, then they can swoop in for the kill—it’ s just an amazing thing to watch.

Essentially, what I want to do with virtual reality is turn people into cephalopods. There’s one other little piece to this, which is, why aren’t cephalopods running the planet? Because they are just amazingly smart. They’re this whole other evolutionary line that generated big brains, and the one secret weapon we have that gives us this planetary rule function—for better or for worse—is that we have childhood. We can accumulate knowledge and wisdom across generations and the cephalopods don’t. Each generation just emerges from the egg and has to learn all over again. If they had childhood they would definitely rule the planet. The way I think of it is a person with really good virtual reality would be similar to a cephalopod with childhood.”

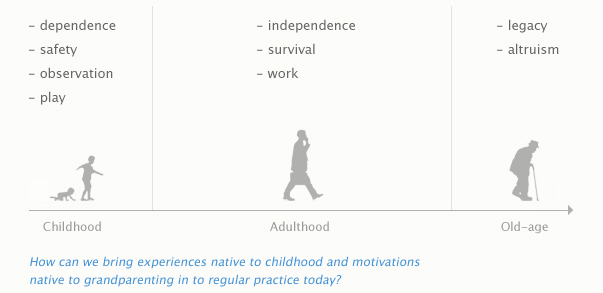

So, both Kelly and Lanier have observed and concluded that childhood and (for lack of a better term at the moment) old age—life stages that bookend the majority of an otherwise uninterrupted, modern human life—are necessary requirements for the long-term advancement that humanity has experienced. In both cases, learning is at the core. In childhood, as Lanier suggests, we have the ability to learn by observation within a context of safety, as our parents protect and provide for us. When I think about childhood, the words that are prevalent in my mind are dependence, safety, observation, and play. Play, especially, is a way we process what we observe, enabled by the safety we have as dependents of our parents. Then later in life, as Kelly points out, we have the perspective from experience to impart wisdom on those younger than us. Likewise, the words that I think of related to old-age are altruism, legacy, and even wisdom. Both stages are now essential to human existence. As modern humans, we value childhood—our objections to child labor are indicative of that—just as we value old-age—our concern for social security and healthcare are indicative of that. Another way of looking at it, of course, is that one stage is where we’ve come from, the other is where we are going.

How Do We Apply This as Designers/Marketers/Technologists/etc.?

With all that in mind, I wonder whether we can take that life-long cycle and miniaturize it as an educational tool now? One of the most common things I hear from colleagues and clients is that while we’re great at identifying goals, we lack the time to achieve them. But I’m now wondering whether the answering the question of when we’re going to find time to do something is really the only thing between us and our goals? What about how we’d use that time if we had it? Taking Kelly’s and Lanier’s points into consideration, I think we could (and probably should) find ways to emulate childhood and old-age when it comes to building in learning-oriented structures to our lives.

It’s not as if there is any lack of educational resources available today. It actually seems that we have at least a part of the grandparent thing already going on: Whether through books, websites, podcasts, online video, meetups, conferences, and a whole host of other means, we have more information available to us from which we can learn than probably ever before, at a lower cost than ever before. These are a manifestation of us giving knowledge back to one another. So, sure, we could all stand to carve out some time to make use of them. But what about play? Just think about all that children have learned before they set foot into their first classroom, as well as all they continue to learn outside of the classroom from that point forward. Play is an incredibly effective learning tool that seems to be completely absent from professional contexts, probably because in most cases play would violate our professionalism or put too much at risk. But what ways could we use play to practice or challenge the things we do?

I don’t have a clear answer on this, but I think it would be valuable, in light of what I assume is a shared value for continued learning, to consider how we can regularly infuse our own adult, professional lives with those things that characterize childhood and “grandparenting.” When we carve out time for professional development, can we allow for play? And then later, how do we best use our desire to share knowledge in a way that is not just serving our instinct for legacy, but is actually altruistic and strengthening to humanity as a whole? Big questions, I know…

“A typical tribe of hunters-gathers had few very young children and no old people. This demographic may explain a common impression visitors had upon meeting intact historical hunter-gatherer tribes. They would remark that ‘everyone looked extremely healthy and robust.’ That’s in part because most everyone was in the prime of life, between 15 and 35. We might have the same reaction visiting a trendy urban neighborhood with the same youthful demographic. Tribal life was a lifestyle for and of young adults.

“A typical tribe of hunters-gathers had few very young children and no old people. This demographic may explain a common impression visitors had upon meeting intact historical hunter-gatherer tribes. They would remark that ‘everyone looked extremely healthy and robust.’ That’s in part because most everyone was in the prime of life, between 15 and 35. We might have the same reaction visiting a trendy urban neighborhood with the same youthful demographic. Tribal life was a lifestyle for and of young adults.  “There could be a future in which communication between people becomes incredibly more rich and intense than what we’ve known so far. Now, as it happens, evolution on Earth is awfully creative and she’s come up with a creature that can do some of that. So, some of the cephalopods—some of the cuttle fish and octopus—can morph. They can just, at will, project images on their bodies and change their shape and turn in to different things. It’s just the wildest thing and they do great stuff with it. For instance, there’s a cuttlefish that hunts for armored crabs and it’s just this soft little thing. They’re kind of like people in that they’re soft creatures that have to live by their wits instead of by their brawn and the way they hunt is by psychadelic art. They turn into these weird morphing displays that just totally stun the crab. So, then they can swoop in for the kill—it’ s just an amazing thing to watch.

“There could be a future in which communication between people becomes incredibly more rich and intense than what we’ve known so far. Now, as it happens, evolution on Earth is awfully creative and she’s come up with a creature that can do some of that. So, some of the cephalopods—some of the cuttle fish and octopus—can morph. They can just, at will, project images on their bodies and change their shape and turn in to different things. It’s just the wildest thing and they do great stuff with it. For instance, there’s a cuttlefish that hunts for armored crabs and it’s just this soft little thing. They’re kind of like people in that they’re soft creatures that have to live by their wits instead of by their brawn and the way they hunt is by psychadelic art. They turn into these weird morphing displays that just totally stun the crab. So, then they can swoop in for the kill—it’ s just an amazing thing to watch.