<— Author Note: I actually started writing this post in December of 2010 (hence the “as it draws to a close” in the first paragraph). For some reason that I can’t recall, I put it aside. Now that I’m in a somewhat retrospective mood, I thought I’d just go ahead an post it—I’m also trying to reduce the size of my “Work in Progress” folder that sits on my desktop. It’s a bit rambly, but I think there’s something here… By the way, the last time I used IRL was back in January, 2009. —>

I’ve spent more time than ever online this year. So as it draws to a close, I’ve been taking some time to reflect upon that and think critically about the content I consume and contribute online, as well as my experiences in real life and how they all fit together in my experience. The trouble is that distinction between real and virtual: What is real, anyway? To what extent is my online activity real or unreal?

It’s funny that the acronym IRL (in real life) has come to signify the online from offline—as if we didn’t already know the difference. But maybe we don’t, or at least, maybe it’s not as clear as we assume it to be.

In a post for his NYTimes Bits blog, Nick Bilton straightforwardly questions the role of technology in our lives and, in my opinion, clarifies the distinction between real and virtual in a few ways.

First, he quotes Clive Thompson, a writer for WIRED magazine:

“We’ve been in a crazy, experimental overload period with online social media for the last two or three years — but I think people are now beginning to figure out a more balanced role these tools play in their lives…A lot of people I know are reaching that inflection point with social tools.”

Then, a bit later, he writes:

“This is most obvious in the darkest of places, including bars and restaurants, where a warm blue sheath of digital paint blankets people’s faces as they stare down into their smartphones, foreheads pointed to one another. They are grazing on a conversation that is not the one taking place before them.”

Thompson’s quote observes that, regardless of the semantic debates over what “in,” “real,” or “life” really mean (read that in your best Bill Clinton voice, please), he is observing an intentional distance that people in his life are placing between them and the technology they use. It’s anecdotal at this point, but it stands to reason that any data we might gather reflecting personal and/or professional technology use would probably come with a lag—that the most current trend is the one you see and experience, not the one you read about after it’s been polled, surveyed, and analyzed. And even if there is no grand trend to speak of—if people don’t necessarily return to a less digital life en masse—the observable calibration is relevant to be sure.

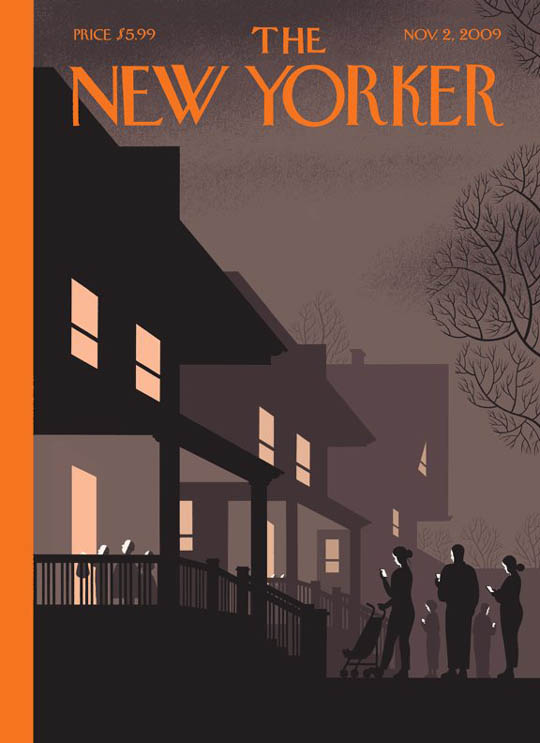

Bilton’s own reflection, which points out the irony in people being distracted from their immediate connections by those they have online, reminded me immediately of my favorite New Yorker cover, from November of 2009, which does exactly the same thing without using any words at all. This image is brilliant. Someone could write a book about it.

It’s strange that the smaller the device, the more at home it makes itself just about anywhere. I mean, somehow, the larger the technology, the more out of place it seems away from a desk, and yet, it’s really only a matter of size, not complexity or potential for distraction. After all, the big, boxy computers we used to use barely come close to being as powerful as our smartphones. Improv Everywhere pointed this out hilariously back in 2008:

For a contrasting view, Mitch Joel, who blogs prolifically at Six Pixels of Separation, recently posted on his irritation with the distinction:

When you’re online, are you fake? Is your online avatar simply that: a representation of who you would like to be instead of who you really are? …People will look at me sideways when I say that online social networks are the real world. They don’t buy it. They think that you can’t create and nurture a “real” relationship online. Anything “real” has to take place in the “physical” world. This is not clear to me. It’s confusing, and it often confuses me when I think about it. I am typing this Blog post right now in the real world. I am using real world emotions. I am using real words. I don’t consider any of this virtual. I don’t consider any of this fake or inauthentic…If we say that everything online is not “the real world,” we are – to some extent – diminishing it, dismissing it and making it seem less substantive than it is…When you’re online there is still a human factor and real collaboration does happen when individuals are not in the same room.”

For me, the distinction isn’t so much about whether my identity fundamentally changes depending upon whether I am on or offline. There’s real and there’s fake in both settings. But, I do feel that the experience of being online versus being offline is fundamentally different. So, I guess IRL isn’t so much about me as it is about experiences. And I don’t think that exploring the distinction is a useless thought experiment, either. I think that the way we understand the ways in which our experiences and interactions change from the physical to the digital world will have a profound effect upon what we design, build, sell, and market.

What do you think?