Most of the successful marketing campaigns that stand out in my memory all revolve around characters. Some of them are simply charismatic spokespeople, like Geico’s gecko, Nationwide’s “Greatest Spokesperson in the World, or, I suppose, Burger King’s creepy king. Others keenly represent the intended customer—think way back to Wendy’s “where’s the beef?” lady, or more recently to Apple’s mac and PC guys. In all of these cases, it was decided that a more compelling message could be created by using characters to tell a story, rather than putting the product itself front and center.

Relating to characters and their stories is essential in order for people to make an initial connection with brands. Sure, some brands eventually transcend the need for connection and become themselves defining characteristics of people. In fact, Apple’s “I’m a mac/pc” was somewhat self-referential in that way. But in the beginning, people need to connect with a story in order to believe that a product or service matters to them.

Of course, this isn’t news. This has been established marketing thinking for a very long time. But somehow, the concept of storytelling doesn’t seem to have worked its way down from the worldwide mega-brands to the next tier of businesses in which you and I work. But why shouldn’t it? After all, we’re endeavoring to speak to the very same people they are!

This month I’d like to explore storytelling, dispel the myth that we can’t tell stories on the web, and identify some ways we can hone our craft as web-based storytellers.

We’ve heard quite a bit over the past few years about how the web has changed the way we read, even the way we think. In particular, the often publicized worry is that the change has been a negative one—that we no longer read deeply, and that we can no longer focus our thinking as we did before. There are plenty of voices in dissent on this opinion, though they don’t tend to dispute the fact that the web has changed us rather than the judgement that said change is for the worse. As a result, those of us in the digital marketing space are caught up in a quite tumultuous time, seeking out any trick we can find to get people to pay attention to our messages online.

But I don’t think there is any “trick” to be discovered. While I may personally worry about the effects of the web on our brains, the reality seems to be that we do not actually have an attention problem. The problem lies in our failure to imbue marketing with information worth paying attention to.

What We Pay Attention To

No matter what happens with the web, people still fervently seek out entertainment. Every year, more books, television shows, movies, music and the like are created and voraciously consumed. But if that is the case, why do we believe this idea that the web has killed our attention? Perhaps the volume of content is increasing but the demands it makes on our attention spans are less? (In other words, is it possible that the web is helping us to create and sell more books, for example, that people aren’t actually reading?) I decided to take a closer look at the books, movies, and television we’ve consumed over the past twenty years to see if a clearer picture of what’s happening might emerge.

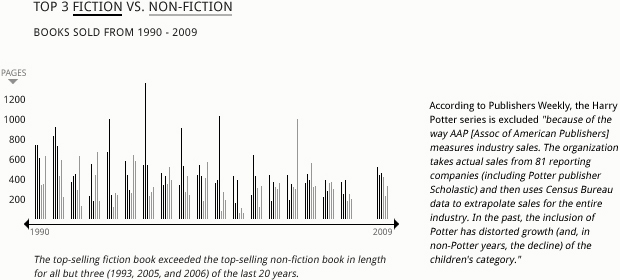

I began by looking at the the top-selling books from the last twenty years, wondering if I might see any trends in length or subject matter. If our attention spans were truly waning, I guessed that shorter self-help books might be the most popular books in recent years. After gathering the top three books from each year, both in the fiction and non-fiction categories (which you can see plotted out in the graph above), I saw that my suspicions were completely wrong. In reality, the bestselling fiction books were longer and outsold the bestselling non-fiction.

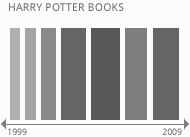

One other aspect of this data fascinated me. You’ll notice that there is a gap where data from 2008 should be. It turns out that one of the most popular fiction series of all time, the Harry Potter saga, completely disrupted the publishing industry’s measuring practices such that 2008 remains unquantifiable. Initially, the Harry Potter books’ sales were recorded in a category devoted to juvenile literature. However, it quickly became apparent that the Harry Potter books were transcending that category. Though it’s known that the sales from this franchise eclipse the sales of any other fiction over the last decade, they’ve been weeded out of the available statistics because of the categorical disagreement. Put simply, if the Harry Potter books were included in the above graph, the length of the best-selling fiction books would be overwhelmingly increasing over time, indicating that reader attention has been consistently captivated by their story. I say “story” rather than “stories” intentionally, because the Harry Potter series is one very long story, told over several books. The reader’s perseverance over the seven books published so far, enjoying a story arc written across thousands of pages (note the increasing thickness of the Potter books themselves in the graph above right), demonstrates an unprecedented dedication of attention.

In other words, people are still reading—apparently, more than ever.

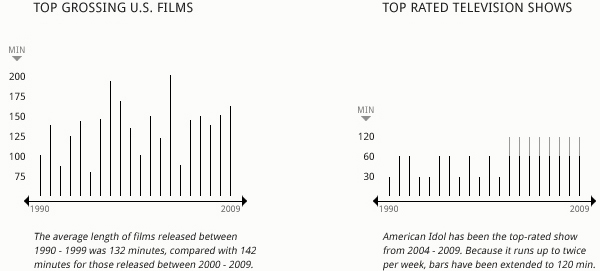

Next, I decided to look at film and television industry data from the same perspective. Anecdotally, my sense was that movies were getting longer, but I couldn’t really be sure (perhaps that’s only true of the movies I watch). So, I gathered the top-grossing movies and the top-rated television programs from the past 20 years and looked specifically at their length. Like the top-selling books, the top-grossing movies and television programs are getting longer.

The television statistics intrigued me in particular. In the years between 1990 and 2000, half-hour sitcoms often received the highest ratings. These shows tended to tell stories that were resolved at the conclusion of each episode, allowing viewers to engage with them easily. However, the popular programs of the last decade have been ones that require more from the viewer. With dramas, one-hour programs with season-length (or longer) story arcs have been more popular. Consider how Lost strung viewers along for 6 years promising resolution to one epic mystery. However, the highest-rated program of the last decade has been American Idol, a reality show. With reality programming, the story is even more personal. Viewers watch as contestants develop over the course of weeks, getting to know them and care about them, and all the more so with those that continue to compete as the show closes in on its finale. Reality shows tell stories that matter to viewers in an even more potent way than fiction in that their subtexts offer a new kind of fairy tale—one that many truly believe could be true for them. That, in a nutshell, is the holy grail of marketing: creating a story that is just out of reach enough to be compelling to people, yet just plausible enough to merit them pursuing it. If nothing else, American Idol demonstrates an extremely effective modern marketing model (how I wish we could do the same with things more wholesome than celebrity, but that’s another column…).

We Pay Attention to Stories

It’s clear from the book, film, and television data that we do not have an attention problem. The common thread here is the power of the story. People want to be told stories, and clearly have an ample supply of attention to give them. Fortunately, the purpose of marketing is to tell a story—one that compels people. Ladies and gentlemen, I think we have a match here…

– – –

Now that we’re certain of the value of storytelling, the pressing question that remains is how to tell stories on the web. I don’t think that the existence of the story is in question—every product or service’s value can be expressed as a story. The difficulty is in framing that story for the people that you know need to hear it. Take some time to remind yourself of that story: What was the problem that you set out to solve? How did you find the solution? Why is your solution special? Why are things different now that you’ve solved the problem? It’s a simple structure, but often one that eludes marketers who are sometimes too close to their product or service to see the story clearly. Once you’re clear on the story, there are two things to focus on next: (1) Writing the story, and (2) making sure that your website supports that story.

Storytelling Requires Good Writing

I, and others at Newfangled, have written quite a bit about the value of writing and the discipline required to do it well. So rather than duplicate that here, let me briefly identify the key principles involved.

- Create Personas: Knowing your story is important, but knowing who needs to hear your story is even more critical. By getting a better understanding of your reader, you will be able to frame your story more particularly to them. Imagine you were telling the story of your first job. You’d certainly tell that story in a different way to a friend over drinks than you would in an interview with a prospective employer. The facts of the story may not change, but the arc and mood certainly would in order to support the point you needed to make by telling it. You can learn more about this in our article on the web development planning process.

- Plan Your Content Strategy: Once you know your story and how to frame it for the people who need to hear it, you need to figure out a practical method for telling it on the web. Keep in mind that your story isn’t only going to be told once. It needs to be told repeatedly in various ways. Your strategy should involve identifying the different kinds of content you will use to tell your story. Perhaps periodic longer-format articles suit your content best, but more frequent blog-format content is more appropriate to your audience. Long-format writing develops and idea in a more in-depth manner contained in one article, while blogs take a cumulative approach to tell an ongoing story with many short posts. But employing both would allow you to build up a large cache of content for different types of readers. You may also identify that other forms of content, like videos, podcasts, e-books, or microblogging should be part of your strategy. You can learn more about this in our article on implementing a value-oriented content strategy.

- Account for Your Engagement Style: It’s safe to assume that writing, or any other content creation, will be a significant challenge. One way to make it easier on you is to identify the ways in which you are naturally inclined to engage with your story at the outset, and use those methods to develop your ideas before jumping in to writing. Without doing this, writing will likely exhaust and frustrate you and keep you from consistently executing your strategy over time. You can learn more about this in our article on making writing easier.

- Pay Attention to Details: All kinds of things can distract readers and keep them from fully engaging with your content. They may be unable to track with your ideas, but if your personas are accurate, it’s probably details of execution that hang them up the most. Look critically at the way you format your articles, making sure they facilitate scanning, include imagery, and include the right calls to action through which a reader can continue her engagement with you. You can learn more about this in our article on best practices for formatting web content.

Enabling Storytelling with User Interfaces

User interface design decisions don’t tell a story on their own, but they can certainly keep a story from being told. The most important thing to keep in mind when determining the functionality of a page is the page’s core purpose. Every additional widget or call to action on a page should either directly support or at least not overshadow it’s main point. Those that do not are more likely to distract your readers than help them focus. This seems obvious enough, but it’s common to take a give-them-everything approach and overwhelm a page’s sidebar with related content or calls to action in the hope that something there might engage a reader. A better approach would be to choose from a selection of options (calls to action or supporting content) the ones that best fits the persona for whom you’ve written the article on the page. Below are three examples of sites that I read from regularly that have mastered the art of keeping their article pages focused on the main content, though they take quite different approaches to layout.

|

|

|

While there’s an obvious beauty to the minimalism of these pages (though I must say I secretly wish every article looked like their print-optimized versions), there is nothing wrong with finding ways to encourage readers to continue their sessions on your site. In fact, I’ve recently noticed a couple of new examples of user interfaces that encourage continued reading that are visually appealing, clever, and helpfully unobtrusive.

Click the image to view this feature in context.

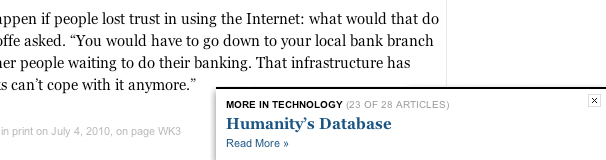

The New York Times quietly added a feature to their article pages which only appears once you reach the end of the article. By subtly appearing once your browser has reached the bottom of the page, this related content offer doesn’t distract you from reading the article at all.

Click the image to view this feature in context.

The Wall Street Journal, on the other hand, has built a related-content tool that is more browsing-oriented. Situated at the top of their article detail pages, their “top stories” ribbon allows you to scroll through related content rather than hunting for it in the standard navigation systems.

Pep Talk

Someone once told me that good design gets out of the way of the message. Once a book has been written, those charged with designing the pages and cover take great care as to create a cover that sells the story and page layouts that simply supports the words. Any more visual attention to the inside would distract the reader. Web design should be the same, but we tend to take the opposite approach: designing and building websites before giving much thought to the content they will contain.

Writing is clearly the first and most important part of telling your story. Even if your content strategy leans more heavily on audio or video than written content, writing still plays a major role in creating that material—articulating the purpose and plan for what is recorded and edited later. Without devoting considerable time toward writing, and investing in the structured work writing requires such that it becomes an established discipline at your firm, the value of your story will be lost. I hope we’ve provided some information and tools to help you along the way.

Meanwhile, user interface trends are changing rapidly based upon new devices and evolving technologies. We must do our best to keep up with this change and be discerning about which shifts to act upon. I believe we’re moving in a healthy direction toward simplicity, motivated less by style and more by what facilitates our stories to be told. After all, this web thing is a work in progress.