%leftsidebar%

#macro:bloglist,3066,agencies#

As I mentioned in last month’s newsletter, this is by no means a comprehensive overview of the possible future of the web. There are plenty of general themes and specific technologies that I won’t cover, and among those that I do cover, probably some disagreement on the finer points, especially in this portion. I welcome your feedback, suggestions, and corrections!

%leftsidebar%

#macro:bloglist,3066,agencies#

My earliest memories of accessing the internet mostly take place in my family’s “office,” where we had a desktop computer attached to a modem. Back then, rooms like this were entryways to the web, and in like fashion, most of us began our “surfing” with portals that attempted to categorize web content in order to create helpful starting points for users. Since then, new search algorithms, laptop computers, wireless networking, and newer mobile devices have made location and “starting point” irrelevant to interacting with the web. In fact, current data suggests that web use away from your desk, whether it be at home or work, is quickly eclipsing the older, one-point-of-entry paradigm.

It’s fairly likely that you own a phone capable of sending and receiving email, accessing and viewing webpages, and even running web applications that allow you to access social networks like Twitter and Facebook. If you don’t, my guess is that you probably will soon enough. You may even own other devices that connect wirelessly to the web, like the iPod touch or the Kindle.

I am among 28.5 million active subscribers to mobile networks using a BlackBerry device. Initially, I found that number to be pretty staggering. That is, until I saw some data pertaining to the iPhone: As of March, 2009, a total of 21.4 million iPhones had been sold, roughly 30% of which were sold in the United States alone. Bearing in mind that the iPhone was only released in December, 2007 (about a year and a half ago), and the original BlackBerry was released in 2002, these numbers suggest a steep increase in mobile device adoption in general. Whether this jump was due to Apple releasing the right device at the right time or people feeling more comfortable with mobile web use now that they can use an Apple device is hard to tell. The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project 2009 survey’s conclusions fall in line with the apparent connection between the iPhone (remember, released in December, 2007) and increasing mobile web use:

“The report also finds rising levels of Americans using the internet on a mobile handset. One-third of Americans (32%) have used a cell phone or Smartphone to access the internet for emailing, instant-messaging, or information-seeking. This level of mobile internet is up by one-third since December 2007, when 24% of Americans had ever used the internet on a mobile device. On the typical day, nearly one-fifth (19%) of Americans use the internet on a mobile device, up substantially from the 11% level recorded in December 2007. That’s a growth of 73% in the 16 month interval between surveys.”

At this point, mobile browsing is not very sophisticated, and therefore probably not the main draw for users accessing the web on mobile devices. The combination of small screens, inconsistent input options, slow connections, and the lack of web content optimized for mobile browsers makes browsing the web from a mobile device browser a pretty clumsy, unpredictable, and frustrating experience, especially if you’re not using an iPhone. However, applications written for mobile environments that deal with specific, limited sets of data, such as Google’s mobile apps, specific device applications for Twitter and Facebook, or the millions of applications in the iPhone apps store, are more likely the future of mobile web use.

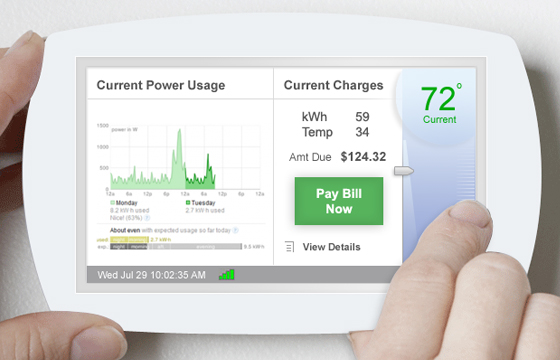

The extension of the web will not be driven solely by personal mobile devices, but also by interfaces in transportation vehicles, homes, clothing and other products. In some cases, the nature of the web enhancement may benefit marketing initiatives, such as web-connected grocery store “VIP” cards, which will continue to track your spending but will also feed your data into a database monitored by intelligent programs in real time and match shoppers with sales and promotions in stores. But in other cases, enabling previously unconnected devices to access the web will actually make them more useful and efficient. In the image below, I imagined what a web-ehanced home thermostat might look like. In addition to being able to monitor your power usage using Google PowerMeter, you’ll also be able to see what your current charges are when it matters to you (i.e. when you’re turning up the heat, not when you’re sitting in front of a computer).

In another example, imagine being able to see a display of your current bank account balance directly on your debit card (pictured below). This data would of course be protected, and displayed only after passing a biometric security protection system that reads your fingerprint directly on the card. I admit, this idea is likely to be much more touchy due to privacy and security concerns, but I’m fairly sure that something like it will exist in the not-too-distant future.

Like the app-specific future of mobile devices, web-enabled appliances and objects will be designed to be good at one thing but not as general-purpose web browsers.

Since I published Part 1 of The Future of the Web, discussion of augmented reality has increased all over the web. This has been an idea that has gone from concept to reality quicker than anything I’ve seen before, which is both exciting and even a little bit frightening. After seeing how this technology might be used, I think you’ll understand why I feel that way. Augmented reality is “is a field of computer research which deals with the combination of real-world and computer-generated data (virtual reality), where computer graphics objects are blended into real footage in real time (Wikipedia definition).” In other words, it is a technology which will allow you to layer web data over images of the real world, whether through webcams, phones or other devices, in real time. Simply Google this topic and you’ll quickly see how many possible applications of this technology, both in nascent stages and purely hypothetical, are already being dreamed up.

In the image below, I imagined what an augmented reality application might display if I pointed my phone’s camera at Newfangled’s North Carolina office. By combining GPS and landmark recognition technology, my smart phone will not only detect and identify both my location at Newfangled’s North Carolina office and my focal point, but will also show web-based information emanating from the office in real time.

The GPS piece already exists, of course, and has enabled working augmented reality applications already, such as one that detects the nearest tube for iPhone users in London. However, the software that would correctly detect and identify the focal point of the image is still in development. Google, for instance, is working on a program for landmark recognition that would learn the identity of a place based upon crowd-sourcing image data and then processing the images to “learn” the attributes of the structure. Also, detecting the actual locations of the people using Twitter and filtering for only those actually at the office when I am looking at it is another missing piece of the puzzle.

Another possibility for augmented reality would be to do for people what we’ll be able to do for places and things. In the image below, I imagine what it might look like if I held my phone’s camera up to Jason Adams, one of our Project Managers. Potentially, an augmented reality application might be able to identify him using facial recognition software, then match Jason with his profiles on various social networks and websites.

Currently, I have to know a person’s name, search for it, and do my own thinking to determine which profiles and pages are actually related to my search. With an application like this one, I could potentially learn quite a bit about a stranger on the bus simply by capturing a quick image. Suddenly, this all got much more creepy, didn’t it? As you can see, Jason is not happy about it, and I imagine many would feel the same. It may even lead to a new kind of digital “masking” technology, the natural response from those that don’t want to have themselves or their property “augmented” for others.

Of course, any of these technologies could eventually be applied to “smart” contact lenses that would make the transition between physical reality and augmented reality even more seamless. That’s not an endorsement, by the way, just a speculation. If it gets to the point where I can’t disconnect, I may head for the hills! As you can see from the example above, augmented reality also stirs up many issues related to privacy, which is what I’ll be discussing next…

%leftsidebar%

#macro:bloglist,3066,agencies#

The headline above is a quote from Zeynep Tufekci, a sociologist at the University of Maryland, who was interviewed last year for a wonderful article in the New York Times called Brave New World of Digital Intimacy. Considering how participation in social media has altered how individuals separate their private and public lives, Tufekci’s comments make me wonder whether such a delineation is even possible anymore. I thought of this recently when a friend posted several photographs to Facebook and tagged me in them. I wasn’t thrilled by this, because I would never have uploaded these photos on my own and now they were visible to a combined list exceeding 500 people! It’s not that there was anything particularly bad going on- they were taken among friends at a restaurant- it’s just that they were lousy images and not flattering to anyone pictured. I consider the tagging part simply bad online etiquette, but am still bothered by the picture existing online at all. Perhaps this is an issue of my own vanity; nevertheless, I now have to consider whether I might appear in someone’s photos that they share online and accept the fact that it’s totally out of my control. At least I can tweak my own account privacy settings to control what I share and who I share it with.

This and other minor issues are no doubt on all our minds as we navigate new social terrain online, but what happens when these issues get really serious?

Concern about online privacy is certainly not new, and if you’re at all like me, each time any controversy arises, the feeling that you have nothing to hide overrides any initiative to really consider the issue fully. But looking at this issue in terms of “having nothing to hide” assumes that if any issue came up, you’d be protected somehow. Brad Templeton, the chairman of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, spoke on this point at the 2009 BIL Conference in a presentation titled “The Evils of Cloud Computing.” In the following quote, Templeton speaks about how the Fourth Amendment protects your privacy, and how it doesn’t:

“One of the things that I am concerned about is erasing the Fourth Amendment. For those who do not know, the Fourth Amendment is the line in the Bill of Rights that mostly relates to privacy. It says that you have the right be secure in your person, papers and effects, and people need a warrant to search your house or search your papers. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court and other courts of the United States have ruled that this wonderful Fourth Amendment does not apply when data is in the hands of third parties.

When you have something on the computer in your house, it is protected by the Fourth Amendment. If you put something on a computer owned by Facebook, it is not protected by the Fourth Amendment. It is only protected in some cases—email has a law that protects email and medical data has a law that protects medical data, and there are laws governing banking records. Specific laws protect certain types of data, but by changing the way we do computing so that all of our data is stored in the cloud we are effectively moving all of our personal data out of our houses and into big data warehouses, and we are erasing a line from the Bill of Rights.We may decide that we want to do that, but I want to make sure that we do not do it casually.”

The choice to put data in “the cloud” is not an inherently bad one; as Templeton points out, we may end up making that choice in the end. However, if we do, it absolutely needs to be a choice that is thoroughly considered and that everyone is aware of. The idea that we might glibly be making critical decisions seems unlikely to us in the present, yet it’s a reality that anyone looking at history in retrospect can appreciate. Recently, a reader named Richard made the following comment on a blog post I wrote about privacy and copyright issues around Google services that profoundly nails the point:

“I think these privacy issues really snuck up on people. We all got used to email, probably with a false sense of privacy. But services like Gmail just make the lack of privacy with email more plain. When you sent an email using AOL or some other service, it was easy to overlook the fact that your words were being passed through many servers and could easily be seen by other people (assuming people cared enough to hack it). Now, seeing ads along side your email makes it much more obvious that your email is not as much ‘yours’ as you thought.”

Richard gets it: We enthusiastically chose to start sharing our data across networks by using webmail services like AOL, Yahoo, and Gmail, but it wasn’t until advertisements related to the content of our emails started showing up on the right of our pages that it really became plain that our messages were being read. Even if it’s just a robot reading them, they are being read- the robot is just a proxy for a person. Imagine if you came home one day and found a robot standing in your hall, reading a letter that had been delivered to your address. You’d be shocked, frightened, and angry, partly because of the robot intruder, but also because it would stand to reason that the robot was reading your letter on behalf of someone else. Though this may be an unlikely scenario, it highlights the need to determine when our information is public and when it is private.

Here’s a more down-to-earth scenario that highlights our inconsistency in the matter: Recently, it took a California court to rule that you can’t simply claim “invasion of privacy” when people circulate what you’ve posted to your MySpace page, even if it’s incriminating. This sets a precedent that we can’t expect protection over the data we willingly share online. When I see stories like this, I think, why on Earth would anyone even think that what is posted on a social network profile is private? A social network profile is intended to be seen by people! But in fairness, issues of privacy are not so cut and dry, and as pointed out by Richard, have almost “snuck up” on us as we naively explored shiny new social network toys online. Clearly, we’re going to have quite a bit of sorting out to do, both in and out of the courts.

Much of the above discussion is predicated on the assumption that you own any data you share about yourself online. But is this really true? There are many indicators that suggest that, despite any conviction you may have on the matter, many companies consider data posted to their networks about you their property.

Stop for a moment to consider how much content you create that actually exists on another company’s server, rather than one you control: Every email you send or receive if you use platforms like Gmail, Yahoo or Hotmail, every event you schedule on Google Calendar, every post you share or comment on in Google Reader, every document you create with or upload to Google Docs, every image you upload to Picasa or Flickr, every video you create or upload to YouTube, Vimeo, Viddler, or Facebook, every wall post, comment, message, group or page you create in Facebook, every tweet on Twitter… believe me, I could go on. For me, except for the content I write for the Newfangled blog and newsletters, much of what I do is on another company’s platform, and it’s a daunting amount! Who owns all this stuff? It seems reasonable to assume that I do if I create it, especially emails or documents, but I’m not certain that’s true, nor am I sure if anyone is.

In the meantime, little issues are popping up here and there that should give you pause. For example, did you know that Twitter restricts data retrieval to the last 3,200 updates a user has entered? Any “tweets” older than that are no longer available to you, yet it seems reasonable to assume that they still exists somewhere. Also, there was a bit of controversy this week when Facebook users realized that their pictures could potentially be used for advertising within the network. While this is indicated by the terms of service agreement that anyone signing up must first agree to, it shows that most people don’t actually read these policies in full before agreeing to them. So what happens if you delete a picture from your Facebook page? It seems reasonable to assume that it gets fully deleted, but there’s no real guarantee of that. Indeed, if a third-party is using it for advertising, it could have been copied at that point to their servers, too. Do you see a trend here? I keep saying, “It seems reasonable to assume.” Perhaps, it is, but that’s a bit ambiguous for legal precedent.

In a recent cover article titled Do You Own Facebook? Or Does Facebook Own You?, New York Magazine contributing editor Vanessa Grigoriadis examined the ins and outs of privacy and copyright concerns specifically related to content that uploaded by users to the social network’s website. She points out that, aside from the individual question of ownership of particular content, extracting one’s self and one’s content from such a vast network as Facebook might be unrealistic in general:

“…the issue was more a matter of a kind of pre-rational emotion than any legalistic parsing of rights. What people put up on Facebook was themselves: their personhood, their social worlds, what makes them distinctive and singular… I’m not sure that we can take ourselves out once we’ve put ourselves on there. We have changed the nature of the graph by our very presence, which facilitates connections between our disparate groups of friends, who now know each other. ‘If you leave Facebook, you can remove data objects, like photographs, but it’s a complete impossibility that you can control all of your data,’ says Fred Stutzman, a teaching fellow studying social networks at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. ‘Facebook can’t promise it, and no one can promise it. You can’t remove yourself from the site because the site has, essentially, been shaped by you.'”

I wish I had more concrete answers to provide here, but the simple truth is I don’t. Most legal issues are decided by precedent-establishing cases, so until enough of them are processed by the courts, I don’t think we’re going to have a very robust or comprehensive legal privacy policy pertaining to online behavior or content. In the meantime, it is imperative that we at least thoroughly consider what we do online, bearing these privacy issues in mind.

%leftsidebar%

#macro:bloglist,3066,agencies#

Earlier, I asked you to consider the amount of content you create that exists in “the cloud,” and I rattled off a somewhat lengthy list to show just how much we depend upon the security of other companies to protect our information. I’d like to return to that list to consider another factor- our environment. This time, though, I’d like to share with you my actual list. If you’re like me, you’ve enthusiastically adopted many online tools that allow you to do work, on your own and collaboratively, in a way that is faster and more efficient than ever before, and, best of all, without creating a mountain of paper waste or requiring expensive “suped up” machines. The list of tools and services you use is what begins to create your digital footprint. As thorough as I attempted to be in listing mine, I’m sure I overlooked some things, but I think the point is clear: this is a lot of information, generated by just one person:

- Google profile information and images

- Gmail chats, emails, attachments, and tasks

- Google Calendar events and event comments

- Google Documents

- Google Reader profile information, blog posts and comments

- Picasa profile information, albums, pictures and comments

- Blogger profile information, blog posts, and comments

- Google Books profile information, book listings, tags, and reviews

- Google Maps profile information, saved locations, and reviews

- Google Analytics data

- YouTube profile information and videos

- del.icio.us profile information, tags and links

- Facebook profile information, wall posts, comments, messages, pictures and videos

- LinkedIn profile information, documents, recommendations, questions/answers, groups, discussions, comments and polls

- Twitter profile information, tweets and direct messages

- Viddler.com profile information and videos

- Flickr profile information, images, tags, and comments

- Goodreads profile information, book listings, tags, comments and reviews

- Slideshare profile information, presentation and comments

- Tumblr profile information, posts, pictures, and audio files

- Archive.org profile information and audio files

- StumbleUpon profile information and links

- Digg.com profile information and links

Taken at face value, “the cloud” appears to be something that would benefit us, both economically and environmentally. It’s clear from the list above that I personally benefit from all these powerful free tools and services. But, when I consider how “the cloud” benefits us collectively, I’m starting to feel skeptical. Even the concept of “the cloud” itself bothers me slightly. It implies a light, airy place (off of the planet, conveniently), where we have seemingly unlimited storage. But when we save information to “the cloud,” what we’re really doing is storing content on a server somewhere- a physical machine– maintained by one of the companies offering their web tools to you. Far from the light, fluffy, natural space we’d prefer to envision, these data centers are not even remotely cloud-like; they are vast clusters of machines spread over acres in a single, climate-controlled, power-sucking facility. As our dependency upon web tools grows, companies like Microsoft, Yahoo and Google will have to build even more data centers than they already have to support us.

When I describe these data centers as vast, I am not exaggerating. Microsoft recently announced the construction of a new data center in Washington state, which will be built to the same specifications of another data center currently under construction in Texas. Each facility will occupy 75 acres, consume an estimated 48 megawatts of power, and cost approximately $550 million. To put the power consumption figure in perspective, 48 megawatts of energy could power 40,000 homes! Microsoft is not the only mega-company constructing data centers of this size. Google has already built 36 data centers and has several others in construction (one somewhat nearby in western North Carolina). As you can imagine, this is all becoming very costly, leaving Microsoft, Google and Yahoo seriously considering an invitation to relocate their facilities to Iceland, where the Invest in Iceland campaign is planning for low-cost, geothermal energy supplied data centers. The environmental impact is of concern, too, even to companies who’s primary motivation to rethink the data center may be financial. Rob Bernard, Microsoft’s Chief Environmental Strategist, has said that the entire data center industry is responsible for 880 million tons of CO2 emissions each year.

If your digital footprint list doesn’t approach the length of mine, you may be wondering why our need for new data centers would be increasing so rapidly. Even if an individual doesn’t use that many “cloud” tools and services, fully using one alone can take up a significant amount of space. For instance, Google offers over 7GB of free email storage to Gmail account holders. Its other applications don’t seem to have a published official storage limit, though one Google forum user estimates that your potential Google Docs limit would be 50GB. Facebook, on the other hand, does not seem to have a stated total limit for storage of anything (text data, photos or videos). In any case, without knowing the specific limits, all of your email, calendar, document, photo, and video data across a multitude of services will quickly amount to a lot of storage! Now consider that amount multiplied by the over 100 million Gmail users, or the over 200 million Facebook users! Now we’re getting the picture.

Considering the relationship between my digital footprint and my carbon footprint concerns me*. Do I really need to save every email? Every digital photo? Every video clip? If I care about how my behavior impacts our environment, perhaps my concept of conservation will have to expand to include the conservation of data, too. This could yield some personal benefits. In fact, it may help us to appreciate things more. Back when cameras had exposure limits per roll of film, we considered each shot more carefully before we clicked the shutter. Now, with digital cameras, there’s no need for that kind of thinking. The storage capability of a camera’s SIM card far exceeds the 24 or 36 exposures of a roll of film. But if we can take as many pictures as we want, and save each one, how valuable will any image be? Digital photography is a pretty easy example- I’ve seen Facebook accounts with over 800 pictures attached to them- but I think the idea of digital conservation could translate to anything we do in the cloud. Why not just save less so that we don’t need data centers that look like towns? There has to be a limit to our ability to sustain our appetite for storage, and discovering that limit will surely shape the future of the web.

*Note that as of this writing, not one person had chosen environmental issues as that which most concerned them about the future of the web in a very unscientific LinkedIn poll I set up. Go ahead and vote if you’ve got an opinion.

%leftsidebar%

#macro:bloglist,3066,agencies#

In the first installment of “The Future of the Web,” I covered the role of corporate websites, how social media will influence the way we index the web, ways that web browsers will change to enable more a more intuitive and holistic experience, and possible applications to help us manage the vast amount of data we collect online. In this second part, I continued the discussion by looking at mobile web technology, augmented reality, legal issues of privacy and content ownership, and the environmental impact of the web.

I hope you enjoyed these two articles, which have been a bit more experimental and more abstract than our typical newsletter. I’d like to check back next year to evaluate some of these ideas in hindsight. In the meantime, if you think I’ve overlooked something really important, feel free to let me know with a comment.

Below are some additional links and resources organized by the topics covered in this newsletter:

Internet & American Life Project 2009 Survey

A The Pew Research Center survey detailing the adoption rates of various mobile technologiesMobile Usability

Jakob Nielson’s Alertbox on Mobile Technology UsabilityGoogle PowerMeter

Michael Surtees’ Daylife Feed of Augmented Reality

This is a Daylife aggregated page of news stories related to augmented reality- definitely a a “hot topic” right now.Layar Application Demo:

Nearest Tube Application Demo:

MyIkea Website Demo:

Brave New World of Digital Intimacy

An article by Clive Thompson dealing with how social media is affecting the way we understand and experience intimacy and privacy.Brad Templeton: The Evils of Cloud Computing

Court: Your MySpace Page Isn’t Private

An ArsTechnica piece about how a college student’s rant against her small town provoked a response that ended up in court.When You Put Data In, You Should Be Able to Get It Out

A blog post about the limits to your Twitter account.Facebook can use your pictures for ads, no permission required

LA Times OpEdDo You Own Facebook? Or Does Facebook Own You?

New York Magazine article by Vanessa Grigoriadis that examined the ins and outs of privacy and copyright on Facebook.

TechRepublic: Big Data Centers = Big Environmental Footprints

TechCrunch: Where Are All the Google Data Centers?

It’s Too Darn Hot

A BusinessWeek article by Steve Hamm about the huge cost of powering and cooling data centers.My Blog Posts about a Digital Conservation Movement