A Realization

We’ve misunderstood search for a long time.

We thought search was about asking questions and getting answers. But it’s not. Not really. It’s never been about that.

I’m going to back that up, as long as you stick with me.

For the last five years, we’ve based most of our digital marketing strategy around search — as we’ve understood it. Which is to say that almost every decision we’ve tended to make has been connected in some way to the assumption that the best experience we can offer is the most seamless path from search to answer. This touches everything, from information architecture to user experience to markup to even the underlying logic of the database itself. Our white whale — the magic search box — lurks beneath the surface of every facet of what we do. And yet, it eludes us. It will continue to do so until we can match the resources of the companies who establish our expectations for what search is and how it works. Rather than wait for that to happen — unlikely as it is — I suggest we consider alternatives.

But regardless of whether it is or is not within reach, the magic search box is, ultimately, a distraction. The longer we chase after it, the harder we strive for it, the farther afield we will be from our actual objective: creating platforms that positively affect the bottom line and can be proven to have done so.

It’s too easy to lose sight of that objective. You see, we’ve been so focused on inbound marketing — which is entirely dependent upon search — that the real advances in design and marketing have been in our blind spot. Why? Because they’re essentially outbound, not inbound.

Last week, I found myself sitting in a crowded conference room hashing out some details with a client who is in the midst of an extremely large and complex e-commerce project. It had already been a long day and we still had plenty more to cover. I was tired. It was a little hot in there. I was adding to the hot air by making a long, wonky, convoluted point about how we should handle search when, all of the sudden, something clicked for me. The foggy mix of user experience, search, and lead development suddenly cleared up, bringing an essential connection between them into view in a way that I’d never considered before. I stopped — mid-sentence — reset, and shared this idea with the client. Whether they sensed this epiphany or thought I was recounting standard operating procedure, I don’t know. But in response, a wave of nodding heads circled the table.

I want to share that connection with you. In fact, I fast-tracked this article to make sure this idea made its way to you as quickly as possible because I want you to put it to use as soon as you can.

But first, we need to review a story we thought we already knew.

What “Search” is For

Search, as we know it, was a necessary innovation. We needed a faster, more precise way to figure out what was actually on the web. Humans — slow, dumb, easily distracted, fickle and sloppy — were no good at it. We’d proven that by building Yahoo 1.0. Manually building lists (good lord, can you imagine?) clearly had no chance of keeping up with the exponential growth of the web. Math and robots, as it turned out, were our only hope.

A couple of guys in a garage figured that one out. Ok, a couple of brilliant computer scientists in a garage. Given the mind-boggling complexity of the web itself — its vastness and intricacy — Google was a clever choice for the name of the search tool they built. They turned a math noun, a googol — one, followed by a hundred zeros — into a verb. Brilliant.

But the initial leap forward wasn’t really a better way of searching for things. It was in gathering things to be searched; figuring out just what, exactly, was out there and organizing it all. Sure, then you need to do some math to match the query with the right thing, and that’s no small task, but that wasn’t the out-of-left-field idea. Sergey Brin and Larry Page must have understood something unique about perspective: Good search might look like a better magnifying glass, but it’s actually a better census.

This is an important point. It means that search has always been about the right way of asking for information.

It didn’t take long to figure out how to make what otherwise might have been a public service into a business. Not a search business, though. An advertising business. It shouldn’t be news to you that Google makes its money by selling the information you drop into its little box to advertisers. Adwords, a program that accounts for about 70% of Google’s advertising revenue, promises its customers a good match between the words and phrases they believe are representative of what they offer and the search queries made by you and me. The more we search, the more ads Google can display. This is a much better business model than trying to charge you and me to search for things, right?

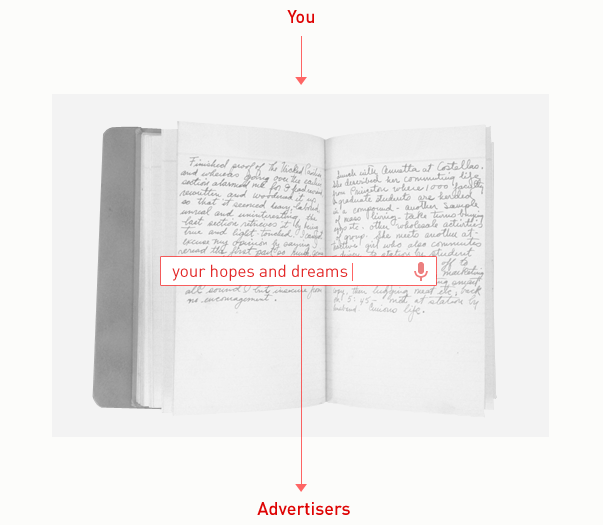

Google’s stated mission is to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Notice that the word “search” isn’t used. It’s really not about search; it’s about Google turning the world’s information — information you and I tell them — into a value proposition to advertisers. You see, it quickly became clear that the world’s information made for something far beyond a better census. Every search query carries subtext that discloses much more than simple demographics. This is what Google sells. They’re saying, “We can match you with people better than anyone else because people tell us everything you want to know: who they are, what they want, what they’re hoping for, what they’re afraid of.” Google isn’t nearly as interested in helping you and me find what we’re looking for as they are in helping someone else find us. To do this, they give us a good magnifying glass; they give their customers the keys to our diary.

Our written diary. The value of that information was made abundantly clear by their $23 Billion IPO (their market capitalization has since exploded to just shy of $300 Billion), but surely there was even more value in obtaining the information we aren’t writing down. That’s where Google Voice came in. The idea was simple: hook up your phone number to your Google account, and Google will turn your voicemails into emails (it does other things too). But it was never really about giving you a better answering machine. It was about Google learning how to build a better machine to interpret the human voice. Why? So that they could give you a new way to search. Why? So that you will keep telling them things. Why? So that they can keep selling access to you to advertisers.

For Google, search is R&D. Plain and simple. It always has been.

Which means that search isn’t really about answering questions. Search is about profiling.

Why Profiling is More Important than Search

These days, I rarely search Amazon.

It’s not that there’s anything particularly wrong with their search. It’s incredible, really. Magical almost! And every now and then, I will search for something very specific — usually to price-check it and add it to a wish list. But if it’s so good, why don’t I use it more?

Because I don’t need to.

The more I shop on Amazon, the more Amazon learns about me. In fact, shopping on Amazon is an incredibly intimate experience — something made possible (in part) by it feeling entirely the opposite. It’s inconceivably big, after all. So big that I feel I couldn’t possibly be noticed by anyone. At least not anyone human. Most people are well aware today that a website as enormous and complex as Amazon is a machine — a manifestation of complex algorithms and massive data centers — operating on automated protocols. When I shop on Amazon, it’s as if I’m wandering around a deserted megastore that somehow still works. There isn’t anyone there but me. No one greets me, no one follows me as I browse the aisles, no one watches me hem and haw over the right pair of shoes, no one rings me up and says, “see you next time.” Funny how this changes my behavior. When a clerk at The Gap asks me for my email address, I’m indignant. But I’ll tell Amazon just about anything. Name; email; address; credit card number; bank account number; the names and addresses of friends and family members for whom I buy and send gifts; what I read, watch, listen to; what I wear; what I eat; what personal care products I use; even where I am right now. I know this because I just logged in to my account to verify that yes, Amazon indeed knows all these things. Amazon computes: “Oh, he’s at work now. He’s likely to buy a book or a keyboard or a power strip.” The anonymity I feel is a seductive illusion that makes me all the more likely to disclose even the most private of information.

Every purchase carries a subtext. And, of course, every combination of purchase is also suggestive. Perhaps even of something so private, few customers would ever intentionally disclose it. When the store sees everything and remembers everything it sees, purchasing is profile-building.

Amazon doesn’t stop there. They leverage a multitude of other user actions besides purchasing to extend and refine their customer profiles. Because of what I tell them — directly and indirectly — they know what things I buy, what things I want to buy, and even what things I might buy someday if I know about them. Then they show them to me. They don’t wait for me to search for them. On Amazon, you don’t even have to buy to be profiled; simply using is profile-building.

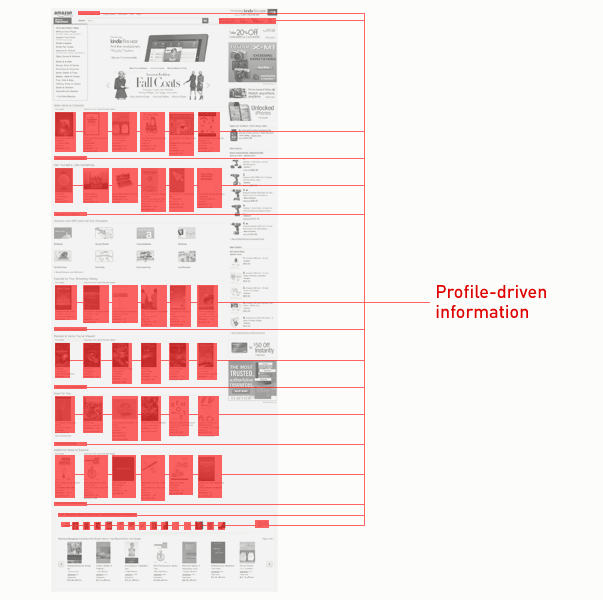

Below is what Amazon.com shows me, personally. I’ve zoomed out quite a bit and used a red overlay to demonstrate just how many things are displayed on the page specifically for me based upon algorithms that weigh the information contained by my profile against Amazon’s inventory. There is a lot of red. That’s because they know a lot about me.

“More Items to Consider”

“Get Yourself a Little Something”

“Inspired by Your Browsing History”

“Related to Items You’ve Viewed

“New For You”

“Additional Items to Explore”

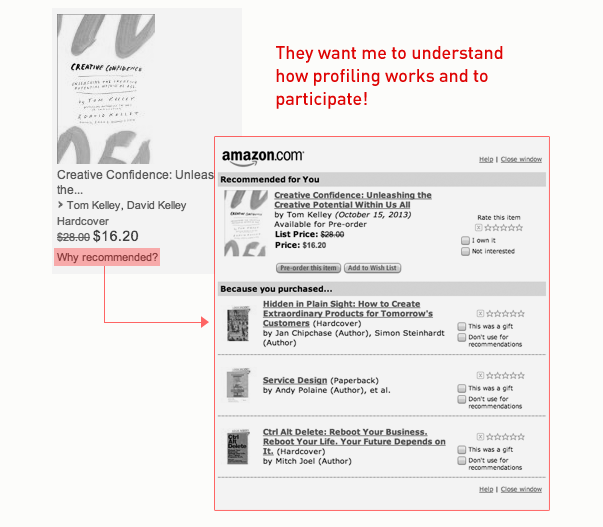

Each of these messages accompanies a list of things Amazon thinks I might want. Each item within these lists is accompanied by a small link that reads, “Why recommended?” which, when clicked, shows me the exact relationship between something I’ve done on the site and their recommendation. They’re not trying to hide how all this works. They want me to participate!

These recommendations fit my profile, which is informed by a combination of the following points of interaction:

- Purchases: Amazon can cross-reference what I buy with what you buy and then show me other things that people like us buy. Also, if I view an item that I purchased previously, I get a helpful “Instant Order Update” message across the top of the page. When I use it to buy that thing again, Amazon takes note of the pattern.

- Wish Lists: Amazon lets me build as many different lists as I want. I can name them, organize them, annotate them, and share them. Some list templates are designed for very specific purposes. A detailed enough gift list can tell Amazon about the preferences of important people in my life. Lists for wedding and baby planning tell Amazon how my family is growing or changing. The metadata within my lists can be just as influential as the products I add to them.

- Browsing History: Amazon keeps track of everything I look at, regardless of whether I add it to a wish list, or put it in my cart. Fortunately, I can edit this, just in case I happen to view The Davinci Code — I was buying it for a friend. FOR A FRIEND!!! — and don’t want Amazon to recommend anything like that to me EVER EVER EVER.

- Prime: Since I decided to pay for a Prime membership — which gets me free two-day shipping, among other perks — I have simply bought more from Amazon. That’s the whole point. I’ve got to shop enough to make the membership worth its price (which, honestly, is not that much shopping). What this does is encourage purchase patterns. When the shipping is free, many things that I might otherwise buy locally become cheaper to buy on Amazon. In particular, a wide variety of household goods. The more I buy that sort of thing, the more Amazon learns about me and my life. (Naturally, I have mixed feelings about all of this. And yet, I am more and more ensconced in Amazon. Look away, I’m hideous!)

This is profiling. It works regardless of my awareness of it, but it works best when I participate. The more I contribute to my profile, the more accurate it is. The more accurate my profile, the better Amazon will be at showing me things. The better Amazon is at showing me things, the more I am likely to buy those things. And the less likely I am to need to search for them.

Within e-commerce settings, search and user experience should have an inverse relationship. The newer the user, the less familiar she will be with the structure, contents, and logic of the platform. Search alleviates that disorientation by making it simple to quickly find the thing you need. But as a user becomes acclimated to the platform — after she has created an account, or made many purchases, or contributed to the sort of profile I described above — search declines in importance. Significantly. It becomes a part of a spectrum of use, not the most important function the site has to offer.

It’s more important that your website be proactive in its personalization than that it has even the most magic of search boxes. The less you expect your customer to search, the longer they will remain your customer.

Don’t make me search. Profile me instead.

This is the connection that became clear to me in the midst of that client meeting. We’d been fussing over an inordinately complex search tool when we should have been thinking about better profiling all along. This is a common mistake, particularly in e-commerce. Far too much time is spent designing bloated systems to get customers to product and far too little on systems that bring product to customers.

How to Get Users to Self-Profile

Now that we understand how profiling can work we need to consider practical ways to introduce it to our users. Amazon, of course, provides a great example. But there are other ways we can increase user input and then use that information to offer a more personalized experience to them. Here are a few to consider:

- Purchases: Your site should keep track of what individual users buy. This requires that your site offer users the ability to create accounts that track this activity, not just make purchases. Once you are tracking purchase history, you can get incrementally better at recommending additional products in whatever ways make sense (e.g. buying profile similarities, demographics, inherent product relationships, etc.) as well as proactively encourage repeat purchases.

- Account Preferences: Your site should ask users to specify their preferences in whatever ways they can map to inventory. What kinds of products are they interested in? Offer them categories so that you can at least reach out to them with new products that they’ll find interesting.

- Wish Lists: The best way to find out what a user wants is to let them tell you without any additional commitment. That’s what wish lists are all about. Sure, they’re handy for users who want to plan and organize their purchases, but more importantly, they’re market research for you. Your site should let users create and manage lists, annotate them, save them, and share them. You should take that information and create automated programs that alert users when items on their list are updated, or on sale, or even just to remind them that they’re available.

- Ratings and Reviews: Don’t underestimate the value of simple, one-click inputs like ratings. Whether its starring items, liking items, or just clicking a cute little heart icon, your website should give users as many low-commitment opportunities for product feedback as possible. Reviews are great, but far more users will be willing to take a fraction of a second to click something they like than even write a brief review for something they love. You can do all kinds of things with this information — everything from finding patterns and promoting products that fit a liking profile to simply reminding a user that a product they liked is on sale.

None of this is creepy. It’s all stuff that customers want to do. They know that this activity translates directly into a better experience for them.

All of their input feeds a profiling platform that will provide you with an abundance of data that you should turn into output. Some of that output will be site-specific — areas designed for personalized promotions, like all those red spots on my Amazon page — but the rest should be off site. Remember what I said at the beginning of this piece? The new stuff — the really advanced stuff — is outbound, not inbound.

Inbound marketing is all about bringing customers to you. Attracting them with content that answers their questions. Informing them. Engaging them. Inbound marketing is a great fishing pole, but we’ve grown up now and we need more than that. We’ve got to scale up our operation. We need to turn our fishing trip into a farming enterprise. We need to reach out, and nurture our audience. We need to start bringing product to them.

Profile data should catalyze offsite, outbound activity like:

- Automated Email Programs: These should be programs designed for specific audience groups that have clear entrance and exit points. For example, you might design an automated program that reminds users of 2-3 products they have in their wish list, and offers incentives to purchase them within a certain time frame. If a user acts on this, they exit that program. If a user ignores it, they might receive an additional reminder before the program ends. This sort of logic could be adapted in many ways. Depending upon the sort of products you offer, it could be as specific as routinely reminding customers when products they have purchased are in need of replacement (e.g. industrial machine parts with measurable life-spans), when warrantees, service plans, or subscriptions are nearing expiration, when new accessories to purchased products are available, or simply when sales are occurring. If you can imagine it, it can probably be done.

- Retargeting: Retargeting will allow you to create offsite advertising campaigns that are specifically targeted to user profiles and behavior. For example, you could use retargeting to show advertising for products that customers have rated or added to wish lists while they are on social networks, like Facebook, or throughout the web. Like automated programs, the specificity of these programs is completely reliant upon the data you are able to glean from user profiles.

These outbound techniques consistently nurture customer interest and proactively bring product to them. They do it in a way that empowers the user. They should always be in control of what they tell you, and have the ability to scale back or opt out of your communications.

This isn’t about search. It’s about being known.

On the web, competition is ruthless. Every opportunity you have to remain top of mind with your audience is one you should fiercely pursue. Your potential customers are looking at your competitor’s website. Your existing customers are looking at your competitor’s website! I assure you of that. So who is going to win their business? Whoever knows the customer best. Don’t make them search. They won’t do it if they don’t have to. They’ll stick with whomever figures that out first. Let that be you. Let them tell you who they are.